Creating the Monster: The American Bureaucracy

Source: http://www.fernbyfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/photo-frankenstein-1931-2.jpg

“The path toward the creation of the modern American state was not linear as some would suspect, but neither was it merely thrown off course by the Progressives in the early twentieth century. It began in the Founding era itself.”

“The most powerful and lasting legacy of Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists is that they set the standard for future political movements that held in tandem state-sponsored economic development, consolidation of political power, and nationalism.” Woods, Thomas E. Back on the Road to Serfdom: The Resurgence of Statism. Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ORD). Kindle Edition.

Good intentions do not always yield good results. Especially when the individuals involved do not understand the complex, interconnected factors of the problems they want to solve. And then there are those that frankly do not have good intentions and seek power for its own sake, regardless of who they hurt. I suspect the American bureaucracy has elements of both and they have created a monster.

This part expands upon The Rise of the American Bureaucracy. The rise is based on:

- The Pendleton (Civil Service Reform) Act in 1883

- The 16th Amendment and 17th Amendments to the Constitution, as well as the creation of the Income Tax and the Internal Revenue Service in 1913

- President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, which significantly expanded the Federal government

- President Johnson’s Great Society with again expanded the Federal government and its scope and reach

I discussed the events in the series on the rise of federal power at the expense of the states. See Part 1: Overview of the Inflection Points.

If anyone is Frankenstein in the opening picture, it is Woodrow Wilson. Wilson championed building a bureaucracy based on Scientific Management principles and expanding it to develop and develop government programs and services. President Johnson is like Igor on Young Frankenstein. The body he selected was Abby Normal, and he helped create Frankenstein’s Monster. In the spirit of Young Frankenstein, Hamilton is like one of Dr. Frankenstein’s ancestors that laid out the theory to create life, little realizing it would create a monster.

Why is the bureaucracy like Frankenstein’s Monster?

First, the creation was not supposed to be a monster in both cases. I seriously doubt that Wilson set out to create a monster. Rather, I think he thought he was doing good. There is a lesson there. Sometimes the best intentions still create bad things when we do not fully understand what we are doing. We can say the same for the mess he created in the aftermath of WWI. We he engaged in bureaucratic reform along the principles of scientific management, I think he genuinely wanted to improve government.

However, human nature is interesting. Wood and the authors in his book discuss the corrosive nature of power and the corrupting nature government freebies. In Wilson’s defense, the 16th Amendment, The New Deal and the Great Society were in the future and few could see them looming on the horizon-unless they understood the true ramifications of the progressives. For example, Wood wrote:

“The more functions the state usurps from civil society, the more the institutions of civil society will atrophy. Once supplanted by coercive government, tasks that people used to perform on a voluntary basis come to be viewed as impossible for civil society to manage in the absence of government—even though civil society did indeed perform these functions at one time. This spiritless population comes, in turn, to look for political solutions even to the most trivial problems.”

The New Deal and the Great Society significantly expanded the power and the scope of the federal government. They also put the government squarely in the business of welfare and making the government the source of people’s finances. This conflicts with the observation of Alexis de Tocqueville, who observed one strength of the American Republic was private organizations promoted the public welfare vice aristocratic (government) organizations:

“If this remark is applicable to those free countries in which monarchical and aristocratic institutions subsist, it is still more striking with regard to democratic republics. In these States it is not only a portion of the people which is busied with the amelioration of its social condition, but the whole community is engaged in the task; and it is not the exigencies and the convenience of a single class for which a provision is to be made, but the exigencies and the convenience of all ranks of life.” De Tocqueville (p. 277)

Edwin J. Feulner, in Assessing the ‘Great Society’ in 2014, estimated the US had spent $22 trillion on 80 Great Society programs. That is an enormous amount of money that I suspect has grown substantially in the last seven years as the government adds more programs and recipients to the mix. I’m not sure where Dr. Feulner got his $22 Trillion figure, but given the nature of the programs and their longevity, I suspect that he is more right than wrong. It represents perhaps the most massive transfer of wealth in history. Did it work or hurt?

Has government involvement solved anything?

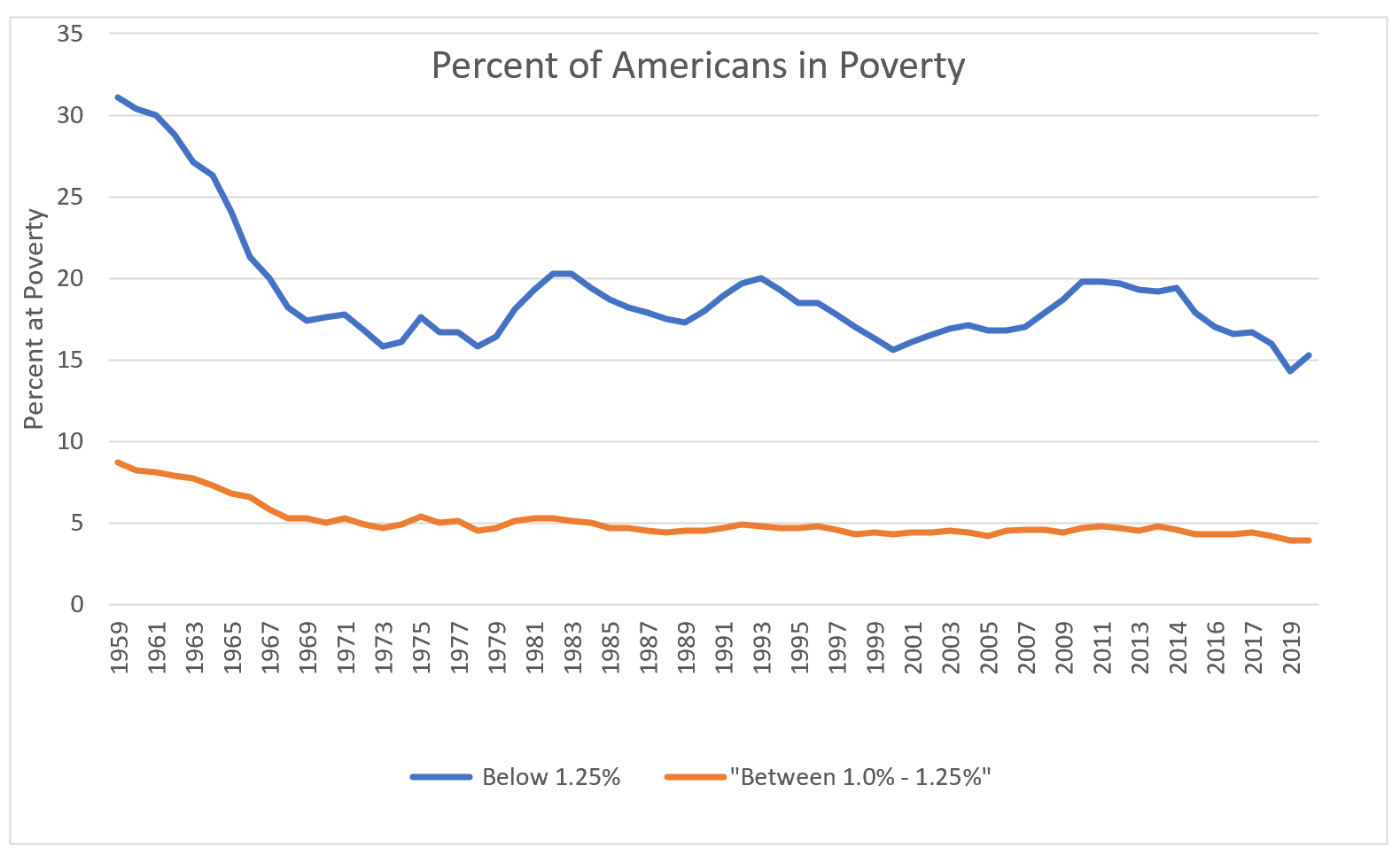

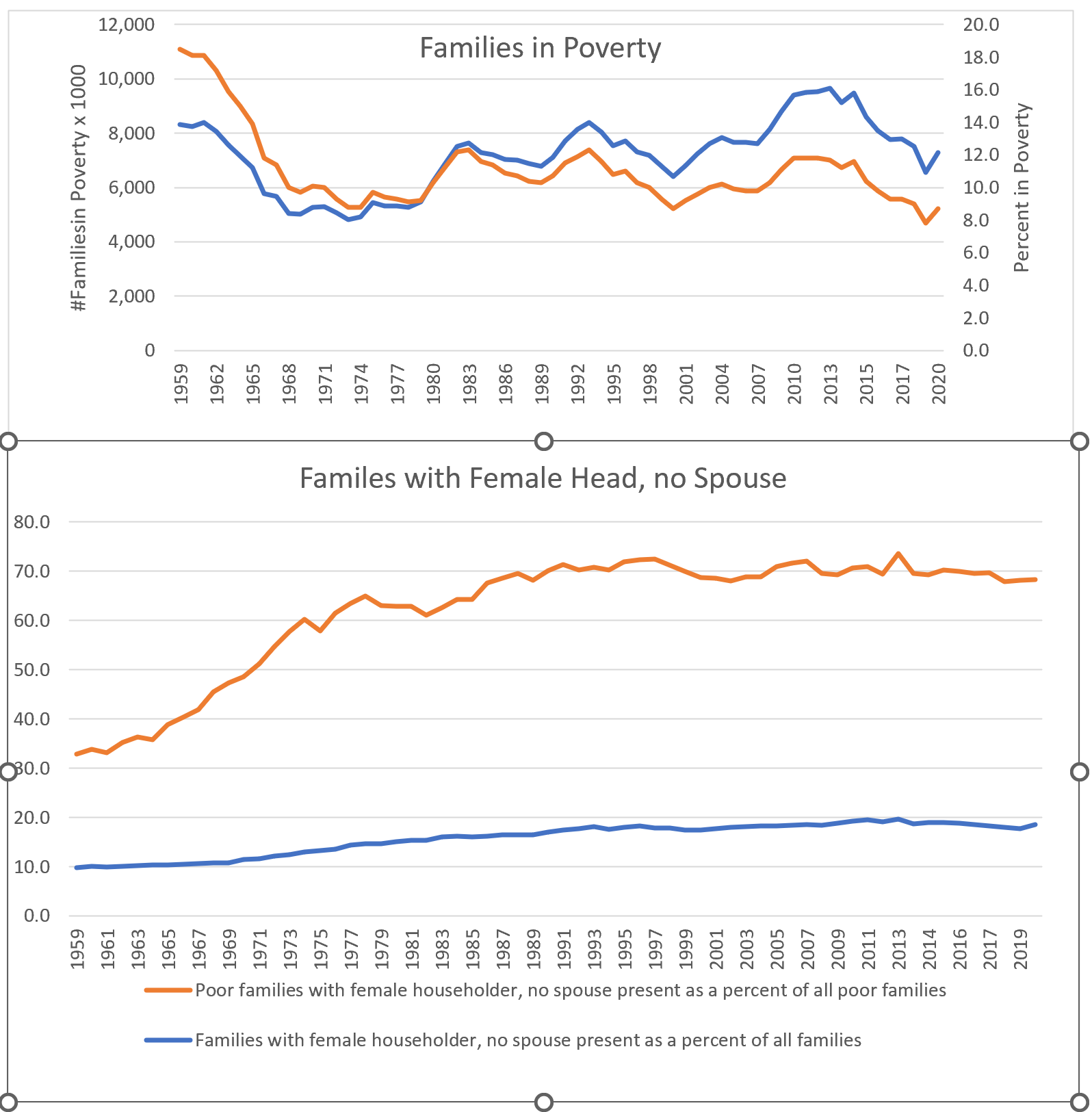

To answer that, let us go to the US census data. The three charts below show US poverty data reported by the Census Bureau. The first looks at all individuals in poverty as a percentage of the total population. Two charts look at families in poverty.

The key takeaways are:

• Poverty was falling before the Great Society legislation started.

• Since the end of the Great Society legislation, the people in poverty have ranged from 10%-15% of the population.

• Since the end of the Great Society legislation, the number of families and the percentage of families has grown and ebbed, but dropped significantly in the three years before COVID.

• The number of families headed by females with no spouse doubled and their percentage of families in poverty grew dramatically.

Almost certainly, economic conditions affect the data too. But the effect, especially on the number of families headed by single women and their explosive rise in poverty, is almost certainly from the Great Society. The government pays many benefits to only families headed by women. This decision changed the family dynamic.

At best, we have spent trillions of dollars to accomplish nothing. At worst, the Great Society programs have wrought considerable damage to the families and structure of America. And the Great Society is not the only part. The FDA has some significant issues and there are allegations that elements of the government and political parties weaponized the FBI, Department of Justice, and the IRS. While that may be too harsh, we certainly need some non-partisan investigation and bureaucratic reform.

Our government has created a monster—a bureaucracy that is accountable to almost no one, given the power dynamics in the theory section below. This bureaucracy includes not only the traditional bureaucracy in the executive branch, but also the Congressional Staff.

Theory

As issues become more complex and the information asymmetries between Congress and the agency increase, congressional control decreases. Congress seeks to rectify this situation and enhance control through broad groups of ex ante and ex post controls, as well as defining the structure of the agency and its processes and procedures. The essence of the literature is to describe how Congress gains and maintains control over the bureaucracy, especially policy setting. Ex ante controls place constraints on the bureaucracy designed to control behavior and policy setting. They include controls, such as process and budget constraints. Ex post controls control the bureaucracy through reporting, congressional hearings, and audits. Congressional controls must allow Congress to shape ongoing policy during a crisis or significant issue. With the State Department, the critical committees are the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. These committees hold hearings and exercise many of the potential ex ante and ex post controls over the State Department.

Moe discusses both ex ante and ex post controls, with a new emphasis on ex ante control (Moe, Forthcoming in 2012). McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast (collectively known as McNollgast) also discuss aspects of political control that are highly relevant to the situation ( McCubbins, et al., 1989). Wood and Waterman also discuss political control over the bureaucracy (Waterman, 1991) and note policy monitoring would help offset some of the asymmetry of information between Congress and the bureaucracy. This information asymmetry is the root cause of many of the congressional-bureaucracy conflicts and congressional desire to place controls on the bureaucracy. Hook states: “Distrust of the State Department and its diplomatic milieu is deeply embedded in US political culture, never far beneath the surface in Congress, the White House, and other agencies of the executive branch.” (Hook, 2003 p. 23). For example, Rondinelli cites House Committee on Foreign Relations to ensure oversight and control of developmental programs (Rondinelli, 1982).

Huber and Shipan provide an interesting study on congressional policy setting that considers presidential and agency preferences as well. They note that Congress implicitly sets policy preferences that recognize the power of presidential veto and the agencies. Congress understands it cannot arbitrarily set policy and define a structure with impunity (Huber, et al., 2002 p. 105). David Lewis continued the advocacy for presidential control over the bureaucracy. He makes the convincing point that the president is the only nationally elected official and is publicly held responsible for policy and performance (Lewis, 2003). While his work, like many others, focuses more on agency design than policy, he does note:

Agency design determines, among other things, the degree to which current and future political actors can change the direction of public policy by nonlegislative means. Some structural arrangements allow more control by political actors than others do. (Lewis, 2003 p. 3)

Of special note for this study is Lewis’ observation, citing Canes-Wrone et al., that

These advantages [over Congress] are perhaps greatest in foreign policy, where the president exercises independent constitutional authority over foreign affairs and maintains the largest informational advantage of Congress. (Lewis, 2003 p. 74)

References

de Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America. Trans Henry Reeve. Pennsylvania State University, Electronic Classics Series, Jim Mains, Faculty Editor, Hazleton, PA 18201-1291 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing student publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them.

Hook Steven W. Domestic Obstacles to International Affairs: The State Department under Fire at Home [Journal] // Political Science and Politics, Vol. 36, No. 1. – 2003. – pp. 23-29.

Huber John D. and Shipan Charles R. Deliberate Discretion? The Institutional Foundations of Bureaucratic Autonomy [Book]. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Lewis David E Presidents and the Politics of Agency Design [Book]. – Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003.

McCubbins Matthew D., Noll Roger G. and Weingast Barry R. “Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative Arrangements and the Political Control of Agencies [Journal] // Virginia Law Review No 75. – 1989. – pp. 431-82.

McCubbins Matthew D. and Schwartz Thomas Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols Versus Fire Alarms [Journal] // American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb., 1984). – 1984. – pp. 165-179.

Moe Terry Public Bureaucracy and the Theory of Political Control [Book] / ed. Roberts Robert Gibbons and John. – Forthcoming in 2012. – Vol. Handbook of Organizational Economics: p. 2.

Moe Terry M “The Politics of Structural Choice: Towards a Theory of Public Bureaucracy” [Book Section] // Organizational Theory of the Organization from Chester Barnard to the Present and Beyond / book auth. Williamson Oliver E. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Moe Terry The Politics of Bureaucratic Structure [Book Section] // Can the Government Govern? / book auth. Chubb John E. and Peterson Paul E.. – Washington, D. C.: The Brookings Institution, 1989.

Rondinelli Dennis A. The Dilemma of Development Administration: Complexity and Uncertainty in Control-Oriented Bureaucracies [Journal] // World Politics, Vol. 35, No. 1. – 1982. – pp. 43-72.

Waterman Dan B. Wood and Richard W. The Dynamics of Political Control of the Bureaucracy [Journal] // American Political Science Review 85 (3). – 1991. – pp. 801-828.

Woods, Thomas E. Back on the Road to Serfdom: The Resurgence of Statism. Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ORD). Kindle Edition.

One Comment

Pingback: