Part 3a – Cognitive 101

Part 3a – Cognitive 101

This is a long, technical piece to provide some background on cognitive issues discussed in the series. It skims the surface of many key issues but provides an extensive bibliography for even more in-depth research if you want more information on these topics. The goal is to show the depth of research and literature on these key topics that are relevant to this series.

Key topics addressed in this part are:

System 1 and System 2 Thinking

The list above is hyperlinked to the parts of this document to provide for easy navigation. It may be handy to have as a companion piece in parts 4-7.

In part 3, I discussed System 1 and System 2 thinking. In a later part, I’ll address cognitive diversity. So, what is this cognitive stuff? This part, designed to play a supporting role in the series and provide background support on some key concepts. You can skip it without compromising the flow of the series but it may help provide a better understanding of the concepts.

Cognitive definition

There is an extensive literature on cognitive/cognition. What is interesting is most of the papers never start with a definition of cognitive/cognition. They seem to take it for granted. Online searches provide definitions as simple as “thinking” or “knowing” to as complex as descriptions of processes such as “the mental process of knowing, including aspects such as awareness, perception, reasoning, and judgment.”

This definitional issue is mirrored in “things cognitive” out in the world. Think of the fracas over The Bell Curve. Think of the recent movements to declare IQ tests and even mathematics racist. Cognition, especially rating cognition, is a societal third rail. Touch it at your own peril. Yet many people write of cognition, cognitive science, metacognition, cognitive behavioral science and cognitive readiness. But few objectively try to put standards in place to measure cognitive capabilities and capacity.

Cognitive Readiness

Cognitive “things” take a better focus with the concept of cognitive readiness. This concept originated in education, but with a lot of educational concepts, it lacked a bit of focus. Two Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA) help to build a conceptual and usable framework. A 2002 concept paper by Fletcher & Morrison (2002, p. I-3) defines cognitive readiness as:

Cognitive readiness is the mental preparation (including skills, knowledge, abilities, motivations, and personal dispositions) an individual needs to establish and sustain competent performance in the complex and unpredictable environment of modern military operations.

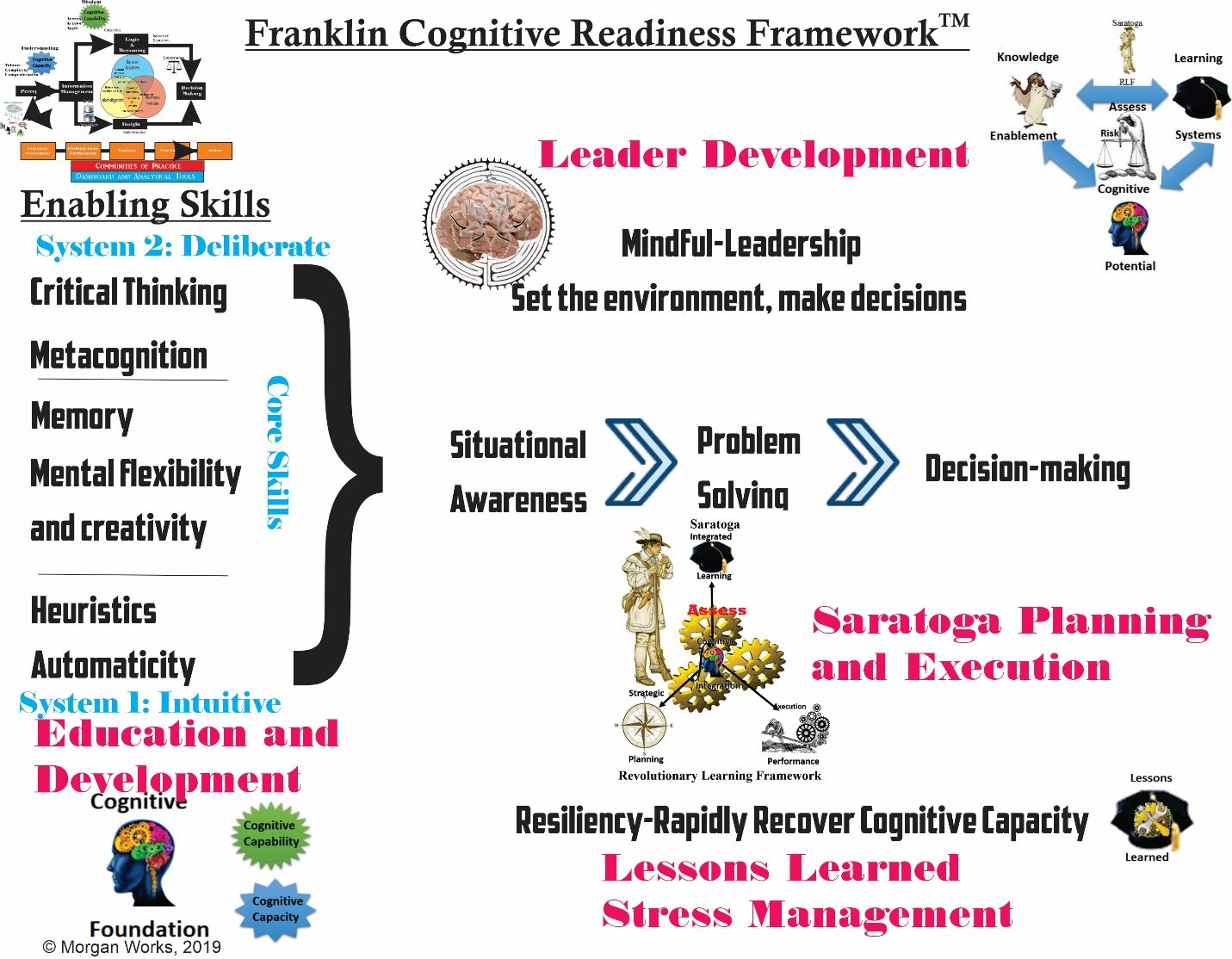

Substitute “modern military operations” with the industry or area of your choice and it is still a good working definition. Figure 1 below takes Fletcher and Morrison’s original conceptual items and adds in elements from my research on cognitive decision-making. The left side of the framework uses elements from Fletcher and Morrison and show how they fit into the System 1 and System 2 thinking discussed in Part 3 and how they facilitate decision-making. The other key parts of the framework are:

- Education and Development to build cognitive capability and capacity.

- Leader Development to build effective teams and cultures that support developing situational awareness and using actionable information to make effective, knowledge-based decisions.

- Integrated planning and execution

- Resilient organizations based on lessons learned and stress management.

Figure 1 Cognitive Readiness Framework

The rest of this part will cover key areas discussed in parts 4-7 of this series.

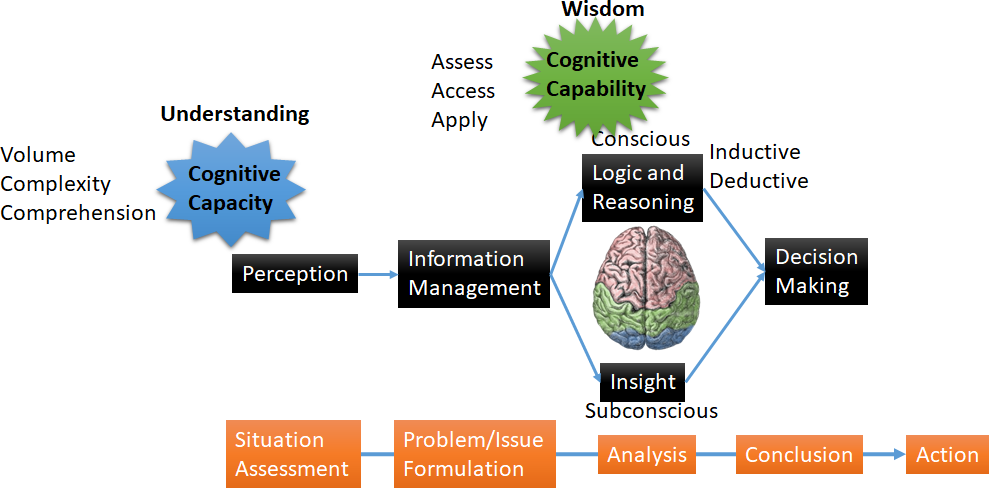

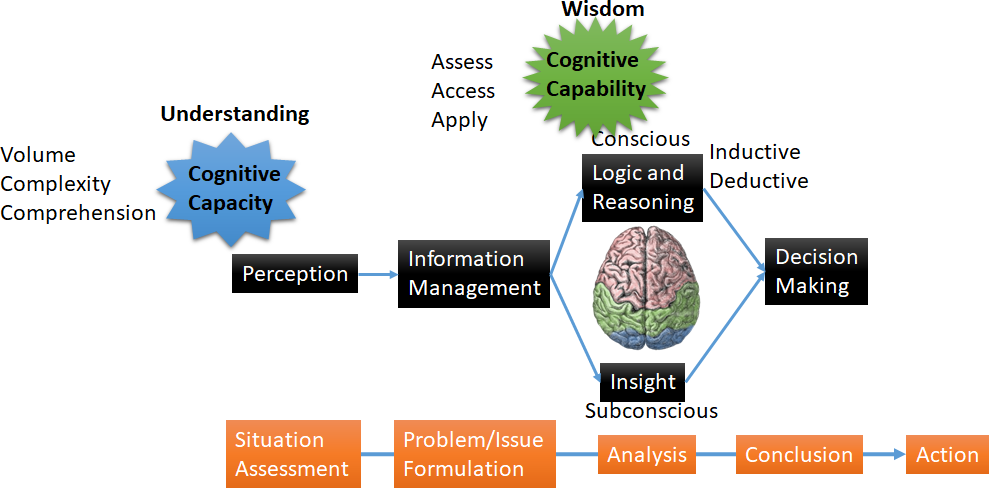

Cognitive Foundation

Figure 2 shows the alignment of cognitive potential to thought processes and decision-making. Cognitive capacity is closely aligned with perception: gathering and building datasets and understanding the situation and data. Cognitive capability is closely aligned with analysis and decision-making. Both support different aspects of information management. These alignments will help to build the simulations and other tools for assessments.

The cognitive requirements to support decision-making should be based on cognitive skills identified in much of the cognitive literature. I have substituted the traditional memory skill with information management and added perception in Figure 91. Information management can include memory, but also reflects the individual’s ability to access various repositories to obtain relevant information. Perception is essentially the ability to recognize and bring in data/information into the cognitive processes.

Figure 2 Cognitive Dimensions and Decision-Making

Logic and reasoning and Insight are the two ways we process and analyze information. Logic and reasoning are primarily a conscious process and can employ both inductive and deductive logic. Insight is primarily a subconscious process. Neither analytical process can work effectively without acute perception and skilled information management.

The black boxes in Figure 2 provide the key requirements for cognitive abilities. The level of skill for each box should correspond to the complexity of the position. Standardized assessments should take out the bias (one of the elements of critical thinking [see Chapter 5]). Critical thinking should go into the development of cognitive assessments.

System 1 and System 2 Thinking

Stankovich and West (2000, p. 658) define System 1 and System 2 as:

“System 1 is characterized as automatic, largely unconscious, and relatively undemanding of computational capacity. Thus, it conjoins properties of automaticity and heuristic processing as these constructs have been variously discussed in the literature.”

“System 2 conjoins the various characteristics that have been viewed as typifying controlled processing. System 2 encompasses the processes of analytic intelligence that have traditionally been studied by information processing theorists trying to uncover the computational components underlying intelligence.”

The framework shown in Figure 1 shows how components of the system fit into a System 1 and System 2 model and integrate them into a holistic approach to decision-making.

The goal is to use critical thinking to test biases and relevant ranges for heuristics. Ideally, we initially engage System 1 thinking to generate initial solutions and then System 2 thinking to refine and test the solutions to select the best, time permitting.

Figure 3 Integrated System 1 and System 2 Approach

Cognitive Biases

Thoughtco provides a nice, quick overview of cognitive bias. They define cognitive bias as “a systematic error in thinking that impacts one’s choices and judgments.” Three other works provide a more in-depth and systemic approach to cognitive biases. Mark Mason in THE COGNITIVE BIASES THAT MAKE US ALL TERRIBLE PEOPLE, Max Bazerman and Don Moore’s Judgment in Managerial Decision Making, and Jeffrey Maynes’ Critical Thinking and Cognitive Bias provide a good overview cognitive bias.

Bazerman and more provide a comprehensive list and description of 12 biases and examples. Many of these get related to the concepts of dogma and belief. What we think we know shapes and influences how we go about solving problems and making decisions.

Dogma and belief and mental models are essentially System 1 thinking masquerading as System 2 thinking. In a paper on policy legitimization, Jensen (Jensen, 2003, pp. 524-525) notes, “Cognitive legitimacy can occur when a policy is “taken for granted,” when it is viewed as necessary or inevitable (Suchman 1995). In some cases, cultural models that provide justification for the policy and its objectives may be in place. In other cases, “taken-for-granted” legitimacy rises to a level where dissent is not possible because an organization, innovation, or policy is part of the social structure (Scott 1995).” The cognitive framework must help decision-makers understand when System 1 thinking drives System 2 type decisions and biases and heuristics inherent in System 1 thought shape or even cut off discourse and dialog.

Cognitive biases impact both deliberate and intuitive decision-making and individual as well as group decision-making. Both Lawson et al and Arnott and Gao note that rules may facilitate decision-making and mitigate bias. Rules may be heuristics or automatically applied rules. Heuristics are highly correlated with System 1 decisions, but groups can use them in System 2 as well. They can also be part of model. The model’s rules may be static or adaptive. In a static model, the rules generally must be manually adjusted. In a adaptive model, Machine Learning (ML) or Artificial Intelligence (AI) may change the rules as it learns the system. However, as Ntoutsi et al note (2020) and Righetti et al (2019), even AI systems may have their own sets of biases.

Cognitive Diversity

The question seems so simple, but the answer is complex. There does not seem to a clear consensus on cognitive diversity, or at least what creates it. Some research tries to develop frameworks that develop characteristics of cognitive diversity, while others look at its effects and relegate the causes of cognitive diversity to other research. In some ways cognitive diversity is similar to Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s test for obscenity, “I know it when I see it.”

From the research, the framework Mello and Rentsch (Mello & Rentsch, 2015) developed and the importance of different perspectives that Mohammed and Ringseis (Mohammed & Ringseis, 2001) discuss are critical. Bender and Beller (Bender & Beller, 2016) bring in the aspect of culture. These two attributes may lead to a military definition of cognitive diversity as the fusion of different perspectives, and traits and experience driven heuristics that that allow an organization to effectively analyze complex problems, develop creative solution alternatives, and decide upon the optimum solution.

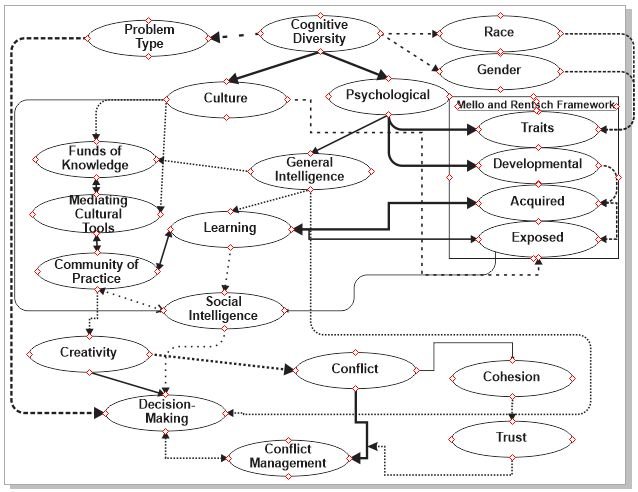

Figure 4 Cognitive Diversity Concept Map

As Figure 4 shows, Cognitive Diversity is a complex area, with many different sources and concepts. This concept map provides a mapping of the key concepts in the literature. Thicker and solid lines show clear concept linkages supported by research. Thinner lines show concepts that are linked, but the research may not mention the concepts directly, such as Funds of Knowledge and Communities of Practice. Dotted lines show concepts that are linked according to some research, but they linkage is either disputed by other research or will need further research to confirm.

Stoyanov et al (Stoyanov et al., 2017) say that cognitive diversity is more important to decision-making than demographics. However, that begs the question of the sources of cognitive diversity and where it comes from. Turning back to Bender and Beller it potentially comes from different cultures, which bring the different perspectives that enhance cognitive diversity. So, does cultural diversity depend upon demographics or can it flow from other factors? For example, the northern US and the southern US have somewhat different cultures and perspectives, but they are not necessarily built upon race and gender. So, if we take Mello and Rentsch as authoritative, they still leave us with the cultural shaping of the Acquired and the Exposed portions of their framework. How do people obtain them? I suspect the answer is through culture and demographics, but Mello and Rentsch play down their role and emphasize Traits, which a more psychological and genetic in nature.

Stoyanov et el (Stoyanov et al., 2017) cite Adaption-Innovation (A-I) Theory and Group Concept Mapping Process (GCM). A-I Theory rates people on style and level. Style ranges from Adaptive to Innovative. Level looks at intelligence, knowledge, experience, and cognitive complexities. As such, Level is similar to Mello and Rentsch’s variables. They use Style and GCM to predict individual behavior and to suggest measures for managing diversity in groups. With cognitive Styles, they bring in the concept of bridgers that help teams to be aware of differences and manage cognitive diversity through awareness of A-I scores. In some ways, this sounds similar to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). While A-I may have the advantage in scholarly acceptance and testing, MBTI has the advantage in access and familiarity.

Pöyhönen (Pöyhönen, 2017) and Baggio et al (Baggio et al., 2019) both show that cognitive diversity is valuable in complex and difficult problem sets, but less so in more routine cases. However, they do not explicitly state whether they focus their study on System 1 and System 2 decisions. Stankovich and West (2000, p. 658) define System 1 as subconscious decisions dominated by heuristics and System 2 as deliberate decisions based on an assessment of alternatives. Their research shows that 80% of the decisions people make are System 1 decisions. Therefore, these two papers potentially miss a critical area of decision-making—the everyday decisions that execute an operational plan. This is especially true with subconscious biases that can sway both System 1 and System 2 thinking. Without cognitive diversity, these biases may be completely overlooked and never be challenged.

Decision-making is also linked to creativity and teamwork. Aggarwal and Woolley (Aggarwal & Woolley, 2019) suggest cognitive diversity can both stimulate and inhibit cohesion and creativity through a signaling process. The key element is how much conflict the competition for cognitive resources cognitive diversity creates. This concept of cognitive diversity engendered conflict parallels Mello and Delise’s (Mello & Delise, 2015) study of cognitive diversity and conflict. They see team cohesion as a moderating force to work through and manage conflict. Mohammed and Ringseis (Mohammed & Ringseis, 2001) also look at cohesion through consensus. Unfortunately, while consensus can facilitate cohesion, it does not necessarily generate effective problem-solving and decisions. We may turn to Follett (Follett, 1995) and Senge (Senge, 2006), however, to find effective ways to manage conflict without sacrificing effectiveness for cohesion. Both authors provide evidence to support constructive approaches to conflict management. Follett suggests that all real progress stems from effective conflict management. Other concepts such as Adaptive Leadership and Adaptive Cultures may also suggest ways to manage conflict arising from cognitive diversity.

Olson et al (Olson et al., 2007) also introduces the concept of trust to help mitigate conflict introduced by cognitive diversity. They qualify trust with “competence-based”. Potentially, the competency is gained through the joint success in solving complex problems. In this case, the trust is developed through success rather than just diversity for diversity’s sake. Rather it is how diversity helps engender success in these complex situations. Stephen R. Covey’s The Speed of Trust may provide some insights into the value of trust and how it can enable effective teams. Adaptive Leadership also places a premium on trust and this concept could help to build this competence-based trust. Culture, especially Adaptive Culture, can also help to promote this trust.

Creativity is important to solving the complex problems identified by Pöyhönen and Baggio. Perhaps this is why both studies cited cognitive diversity is only relevant on complex problem sets and may be the key that both Aggarwal and Kim et (Kim et al., 2020) facilitate creativity over conflict. Both studies cite cognitive diversity can both stimulate and inhibit creativity. In less complex situations, the value of the solution may not provide a significant momentum to overcome the cognitive diversity induced conflict. Working through complex situations provides the challenge to overcome the cognitive friction and help to create cohesion and identify “bridgers” regardless of whether A-I scores are known.

If we use Mello and Rentsch as an initial framework, then additional research needs to validate their criterion variables across a larger study group and determine impacts of variable manipulation. As part of this study, researchers may want to review how these variables arise and the impacts of demographics to confirm Stoyanov et al’s conclusion that demographics are less important than “cognitive diversity”. Are demographics a key element that creates cognitive diversity or, as Mello and Rentsch suggest, Traits are the primary driver of cognitive diversity and hence are more based on individual psychology and genetics?

The second key area to explore is the cultural impact. There are several areas that research can assist in the cognitive diversity realm. Can research support the inclusion of Funds of Knowledge and Communities of Practice to help enable and enhance cognitive diversity? On the surface, the findings from Bender and Beller seem to point they could be the vehicles into seek more diversity and to effectively include it in problem solving. Second, what elements of culture support development of cognitive diversity? This may be especially relevant for the Acquired and Exposed variables in Mello and Rentsch’s framework, well as the A-I theory Stoyanov et al cite. How much of these variables are genetic and how much are cultural?

Another key area for research is the impact of cognitive diversity on problem-solving and decision-making. Both Pöyhönen and Baggio et al found cognitive diversity is beneficial only in difficult and complex cases. Their studies were limited to single fields and, while unstated, seemed to be limited to System 2 decision-making. Further research may help to verify whether cognitive diversity helps to reduce biases that can impair System 1 type thinking. It may also help to show whether cognitive diversity helps to build more reliable heuristics that are critical to System 1 thinking and decision-making.

Cognitive diversity induced conflict is a critical study. While Follett and Senge discuss conflict extensively, they do not necessarily look at conflict engendered by cognitive diversity. The research that shows cognitive diversity applies to complex situations may be key to new research that looks at the value of creating cohesion through solving complex problems. Does the act of solving complex problems as a group overcome the friction of cognitive diversity and create the conditions where teams can jell together. Is there an optimal amount of complexity that helps a team overcome the cognitive diversity engendered conflict? Is there a way to achieve an optimal balance of cohesion, consensus, and conflict to develop effect solutions and make effective decisions?

As we continue to refine our approaches to conflict, more research into trust, adaptive leadership, and adaptive cultures may help to validate Olson et al’s approach to competence-based trust. This could be combined with research on the relationship between cognitive diversity and complex problems as well as validating the value of cognitive diversity in mitigating the impacts of bias on System 1 thinking. Does trust help identify hidden biases so cognitive diversity shows relevance for both System 1 and System 2 thinking, regardless of the level of complexity and difficulty.

Decision-Making

The ultimate objective in the Cognitive Readiness Framework is effective decision-making. As part of their discussion on Knowledge Management facilitation of decision-making, McKenzie et al discuss three types of decisions (McKenzie et al., 2011, p. 406) :

- “Simple decisions are not necessarily easy decisions but cause and effect linkages are readily identifiable and action produces a foreseeable outcome.

2. Complicated decisions arise less frequently. Cause and effect linkages are still identifiable, but it is harder. It takes expertise to make sense of the situation and evaluate options.

3. Complex decisions have no right answers. Although infrequent they have big consequences. Cause and effect are indeterminable because of interdependent factors and influences. The outcome of actions is unpredictable; patterns can only be identified in retrospect.”

These three categories provide a useful way to bin decisions and potentially govern how they are processed in decision systems.

Akinci and Sadler-Smith (2018) write about the intuitive aspects of decision-making, which can bypass structured decision-making processes. They focus on the collaborative aspects of knowledge-building that can create a group intuition and learning. They wrote, “Organizational learning occurs as a result of cognitions initiated by individuals’ intuitions transcending to the group level by way of articulations and interactions between the group members through the processes of interpreting (cf. ‘externalization’) and integrating, and which become institutionalized at the organization level” (Akinci & Sadler-Smith, 2019, p. 560). Akinci and Sadler-Smith then bring in Wieck’s work and the concept of System 1 and System 2 thinking. The intuitive decision-making is a System 1 and the structured approach is a System 2 approach.

Lawson et al (2020) and Arnott and Gao (2019) bring in System 1 and System 2, also discussed as thinking fast and thinking slow. Lawson et al focus more on individual decisions, which may or may not require a decision-making system. They find that having the “right” rules and cognitive faculties are key to effective decision-making as well as mitigating decision bias. Arnott and Gao discuss these in terms of Behavioral economics (BE) and discuss ways to incorporate BE into structured decision-making and Decision Support Systems (DSS). They cite the work of Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman in this field and cite his work on bounded rationality and how it affects decision-making. In this work, Kahneman also discusses System 1 and System 2 thinking and the concept of cognitive biases. An effective decision-making system must recognize cognitive biases.

McKenzie at al (2011) discuss how knowledge management (KM) may help mitigate bias and facilitate other aspects of decision-making. Like Lawon et al and Arnott and Goa they cite Kahneman a great deal. They discuss the impact of emotions and biases on rational choice and how KM can mitigate it. Table II in their paper provides KM approaches to common cognitive biases (McKenzie et al., 2011, p. 408). Ghasemaghaei (2019) concurs that KM is an integral part of decision-making and discusses how KM can help to manage data’s variety, volume, and velocity. Their findings also indicate data analytic tools enhance the sharing of knowledge sharing improves decision-making quality.

Selected Bibliography

Akinci, C., & Sadler-Smith, E. (2019). Collective Intuition: Implications for Improved Decision Making and Organizational Learning. British Journal of Management, 30(3), 558–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12269

Arnott, D., & Gao, S. (2019). Behavioral economics for decision support systems researchers. Decision Support Systems, 122(February), 113063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2019.05.003

Aven, T. (2018). How the integration of System 1-System 2 thinking and recent risk perspectives can improve risk assessment and management. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 180(July), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2018.07.031

Bazerman, Max H, Moore Don A.. (2009). Judgment in Managerial Decision Making (7th ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

Crameri, L., Hettiarachchi, I., & Hanoun, S. (2019). A Review of Individual Operational Cognitive Readiness: Theory Development and Future Directions. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 001872081986840. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720819868409

Fatkin, L. T., & Patton, D. (2008). Mitigating the effects of stress through cognitive readiness. Performance Under Stress, (September), 209–229.

Fletcher, J. D. , Morrison. John. (2004). Cognitive Readiness: Preparing for the Unexpected. Science and Technology Support for Training Transformation and the Human Systems Technology Area, (IDA Document D-3061), 16. Retrieved from http://www.mil.no/multimedia/archive/00064/2_4_USA_Preparing_fo_64451a.pdf

Ghasemaghaei, M. (2019). Does data analytics use improve firm decision making quality? The role of knowledge sharing and data analytics competency. Decision Support Systems, 120(January), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2019.03.004

Grier, R. A., Fletcher, J. D., & Morrison, J. E. (2012). Defining and measuring military cognitive readiness. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, (August 2016), 435–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181312561098

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

Khatri, V., Samuel, B. M., & Dennis, A. R. (2018). System 1 and System 2 cognition in the decision to adopt and use a new technology. Information and Management, 55(6), 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.03.002

Kim, T.-Y., David, E. M., & Zhiqiang, L. (2020). Perceived Cognitive Diversity and Creativity: A Multi-Level Study of Motivational Mechanisms and Boundary Conditions. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 0(0), 1–15.

Lafond, D., DuCharme, M. B., Gagnon, J. F., & Tremblay, S. (2012). Support Requirements for Cognitive Readiness in Complex Operations. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 6(4), 393–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343412446193

Lawson, M. A., Larrick, R. P., & Soll, J. B. (2020). Comparing fast thinking and slow thinking: The relative benefits of interventions, individual differences, and inferential rules. Judgment and Decision Making, 15(5), 660–684.

McKenzie, J., van Winkelen, C., & Grewal, S. (2011). Developing organisational decision-making capability: A knowledge manager’s guide. Journal of Knowledge Management.

Mello, A. L., & Delise, L. A. (2015). Cognitive Diversity to Team Outcomes: The Roles of Cohesion and Conflict Management. Small Group Research, 46(2), 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496415570916

Mello, A. L., & Rentsch, J. R. (2015). Cognitive Diversity in Teams: A Multidisciplinary Review. Small Group Research, 46(6), 623–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496415602558

Morrison, J. E., & Fletcher, J. D. (2002). Cognitive Readiness. October, (October), 48. Retrieved from http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA417618

Olson, B. J., Parayitam, S., & Bao, Y. (2007). Strategic decision making: The effects of cognitive diversity, conflict, and trust on decision outcomes. Journal of Management, 33(2), 196–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306298657

O’Neil, H. F., Perez, R. S., & Baker, E. L. (2014). Teaching and measuring cognitive readiness. Teaching and Measuring Cognitive Readiness, 9781461475(June 2014), 1–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7579-8

Pöyhönen, S. (2017). Value of cognitive diversity in science. Synthese, 194(11), 4519–4540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1147-4

Righetti, L., Madhavan, R., & Chatila, R. (2019). Unintended Consequences of Biased Robotic and Artificial Intelligence Systems [Ethical, Legal, and Societal Issues]. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine, 26(3), 11–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2019.2926996

Schwenk, C. R. (1990). Conflict in Organizational Decision Making: An Exploratory Study of Its Effects in For-Profit and Not-For-Profit Organizations. Management Science, 36(4), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.36.4.436

Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline (Kindle). Crown Publishing Group.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2003). “Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 26(4), 527. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X03210116

Stoyanov, S., Jablokow, K., Rosas, S. R., Wopereis, I. G. J. H., & Kirschner, P. A. (2017). Concept mapping—An effective method for identifying diversity and congruity in cognitive style. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.015

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things that Gain From Disorder. Random House.

Taleb, N. N. (2010). The Black Swan: The Impact f the Highly Improbable (2nd ed.). Random House.

Walston, J. M., Thomas, J. F., Wiswell, J. L., Anderson, J. R., Bellolio, M. F., Hess, E. P., & Cabrera, D. (2014). 135 How Accurate is “My Gut Feeling?”: Comparing the Accuracy of System 1 versus System 2 Decisionmaking for the Acuity Prediction of Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 64(4), S48–S49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.161

Part 1: Justice, Judgment, and Diversity

Part 2: Standards

Part 3: Judgment, Standards, and Cognition

Part 3a: Cognitive 101

Part 4: Policy Development and Analysis

Part 5: Critical Race Theory and the Military

Part 6: Cognitive Diversity Experiment

Part 7: Conclusion

Series Flow