Critical Thinking: Bounded Rationality and Time

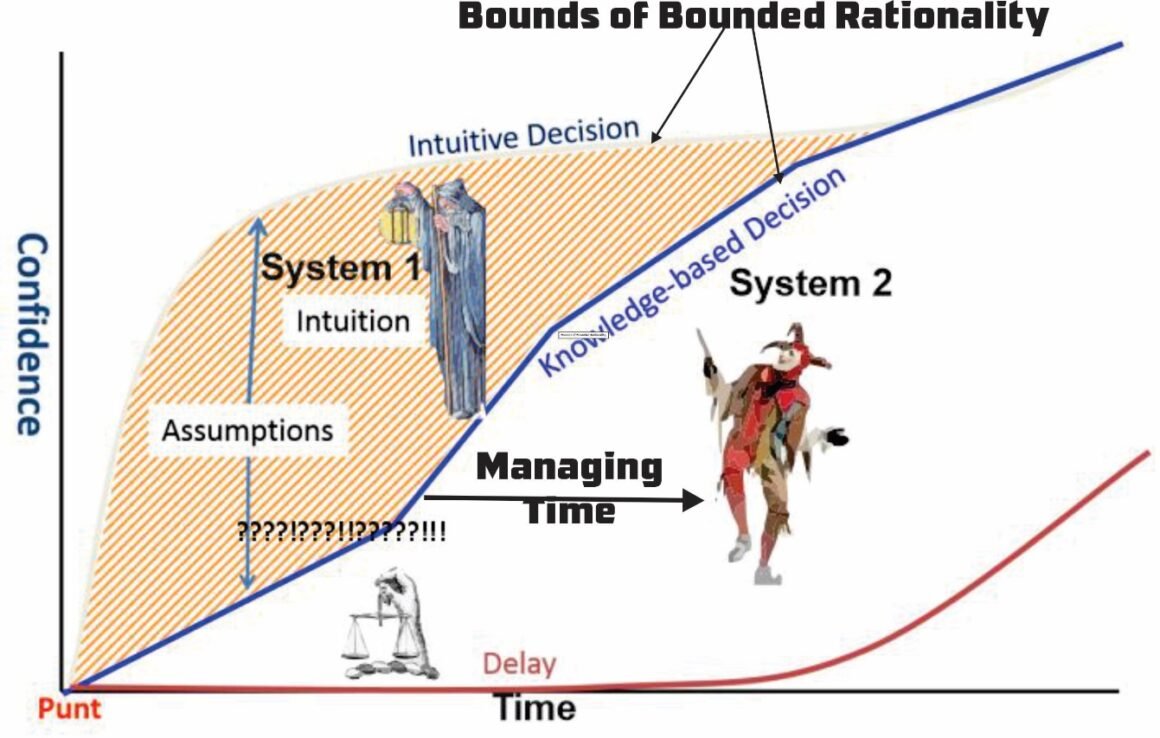

Time is one component of bounded rationality. The Bounded Rationality Model (see the introduction to this series) includes cognitive limitations and information/knowledge quality. Severe time constraints can drive a decision to System 1 approaches, with the decision based on assumptions, heuristics, and intuition. Some organizations “punt” and refuse to decide, fearing the consequences or they can try to delay it to gain more information. But they will never gain perfect knowledge. For practical purposes, the blue line above is the border of bounded rationality.

I’m not sure, however, that time is an attribute of cognitive capacity. For me, cognitive capacity is our ability to absorb information. The higher the cognitive capacity, the more information we can absorb and the more varied the sources we can correlate and integrate. Cognitive Capability is a measure of how we can employ that information. I discuss this at length in my book, Thrive in the Age of Knowledge, available on Amazon. Time stands on its own and limits the decision-maker’s ability to employ cognitive capacity and capability, but does not alter them. They need to be developed and trained to achieve their potential.

The time component of bounded rationality determines how long we can gather and process data to make a decision. That can affect both quality and quantity of the data and information we can access at a decision, but not the actual capacity.

Perhaps a better way to look at is the old calculus model of water flowing into a bucket through one hole and out of the bucket in another. If you took calculus, that was the initial model for δt/δt. Perhaps cognition is similar, with information coming into one hole and actionable knowledge going out the other hole.

Perhaps a better way to look at is the old calculus model of water flowing into a bucket through one hole and out of the bucket in another. If you took calculus, that was the initial model for δt/δt. Perhaps cognition is similar, with information coming into one hole and actionable knowledge going out the other hole.

The water flow figure illustrates this process. The system pulls water from the well and into a pressure tank. The pressure tank then feeds water to the house, represented by the shower. There is a spigot before the pressure tank that lets the system divert water to other uses as required. When someone takes a shower, a few things happen. First, it takes time for the water in the shower to get hot. Second, it pulls water from the tank and the pump needs to pull more water from the well to refill the tank. If other people are using the water, say a washing machine, dishwasher or another person taking a shower, there is a competition for water. If the pressure tank is large enough, it can service the entire demand. If it is not, then pressure drops across the system and the people taking a shower may suddenly find themselves in increasingly cold water.

So what does this have to do with time?

If the first person taking a shower does not wait for hot water to flow through the pipes, he or she will have an initially cold shower. If others do not wait for the shower and other diversions to finish, they divert pressure and hot water and all users will feel the difference. The three big determinants in the system performance are:

- Pressure tank capacity. The larger the capacity, the longer it takes to run out. Does the tank have the required capacity?

- Pump and well performance. Does the pump have the power to pull water from the well fast enough to replace the water flowing out of the tank? Does the well have enough water?

- System use. How many applications draw from the pressure tank concurrently and are there any water diversion from the pressure tank before the water even gets into the tank?

These three determinants act through time. Do we have the time to let the water heat? Why didn’t we wash the clothes we need for that key appointment earlier? Why are the kids filling their swimming pool now for their planned swim party? Why did I spend so much time working on the presentation before I took a shower? Why are we washing dishes now? Could they wait? Could we have sequenced requirements better to avoid a time constrained application of resources? δt/δt or the net flow Δt is a key system constraint in this situation.

So how does taking a shower in a household water system relate to making decisions in an organization?

Rather than water, in a decision system, we look at the flow of information and the development of actionable knowledge. Time is a factor in this flow. If decision-makers cannot gather all the information they need in the allotted time, they are deciding under uncertainty. Virtually every decision has some uncertainty, as shown in the lead figure.

Key questions include:

- Why is time a constraint on the decision?

- Who makes it the constraint and validates the time requirements?

- How complex is the situation and how many variables are there?

- What are our knowledge gaps?

Are the time constraints inherent in the problem/situation or are they an artefact of organizational processes and politics? Are the time constraints validated or are they assumed? Effective leadership assesses these questions and buys as much time as possible. They can do this by restructuring the problem into phases, more clearly defining the issues, or speeding up data collection and processing the data into actionable knowledge. The latter option expands the boundary of bounded rationality and provides room to assess the relevant ranges and their impact on facts, assumptions, and questions.

Let us go back to the water system model and focus on the green text, starting with the leadership function.

Leadership is at the pressure gage in the system. Leaders must monitor pressure and strike a balance. Likewise, they need to monitor the exogenous load that can compete for resources with the decision. The more the leader can divert exogenous loads from the team working the decision, the more potential time savings, the more the organization can push the boundaries of bounded rationality. The leader also needs to ensure the planners assess the situation, and identify critical path tasks, knowledge gaps, and relevant range issues, and, when possible, root causes and the impact on the organization. These activities can help to expand the boundaries of bounded rationality and ensure that heuristics and intuition are reliable and the team implements some degree of System 2 thinking.

The “plumbing” for data and information flow includes the pipes and the Information repository.

The pipes are the bandwidth within the system. Bandwidth issues can slow down all components of both System 1 and System 2 thinking. The bandwidth refers to both the physical bandwidth with the information systems and the person bandwidth of team members and the team. Leaders need to assess this team bandwidth and ensure they focus on the critical aspects of the problem and are not spinning their wheels. Friction erodes time management and can shrink the borders of bounded rationality.

The information repository affects what information the team can access, how they can access it, and how fast they can get it. An effective repository allows for easy queries to get the relevant information and tools to transform it into relevant, actionable knowledge. The greats the capacity and capability, the more the team can extend the boundaries of bounded rationality.

The quality of the repository also depends on the quality of data. The better and more relevant the data sources, the faster the team can employ it. Some data is just noise, some is relevant and reliable, some is relevant, but not reliable, and some can appear to relevant but is not. The repository should clearly identify the data sources and their relevance and reliability. Thrive in the Age of Knowledge provides tools to assess and score data sources and to maintain an effective repository.

The showerhead represents this employment and set of tools and processes. The cleaner the showerhead and the more throughput, the better the shower and the better the decision.

The more leaders ensure the quality of data, the structure and use of the repository and the associated decision support tools, the faster the team can employ them in a crisis. Upfront preparation and planning can save hours, perhaps days of time in a decision and expand the boundaries of bounded rationality.