Critical Thinking: Logic and Rationality

This blog builds on Critical Thinking: Decisions and System 1 and System 2 Thinking. If you are unfamiliar with these concepts, you may want to review this piece.

Citizens of the Republic own the Republic. Not politicians, Congressional staffers, or regulators. But we often lose sight of this salient issue and treat the politicians and bureaucrats as our superiors and often do not question them as effectively as we should. This is especially true in complex regulatory issues. Many of us have not heard of the concept of regulatory capture, but it is alive and well in politics and can lead to significant conflicts of interest or outright corruption. The owners of the Republic cannot blindly accept the words from politicians and bureaucrats, but need to engage in critical thinking to test and validate their policies and directives.

The concept of Regulatory Capture (Reg Capture) typically refers to a phenomenon that occurs when a regulatory agency that is created to act in the public interest, instead advances the commercial or political concerns of special interest groups that dominate an industry or sector the agency is charged with regulating. When regulatory capture occurs, the interests of firms or political groups are given priority or favor over the interests of the public. CFA Institute

Complex problems are the realm of System 1 thinking. Yet many of us skip our own System 1 thinking and use System 2 when we consider political and policy issues. When we do this, we make the implicit assumption that “our side” is truthful and knows what they are talking about. History does not favor that concept and abbreviated System 1 thinking can lead to serious problems. Citizens in a Republic need to think critically about these issues and engage in System 2 analysis and demand policy makers do so as well.

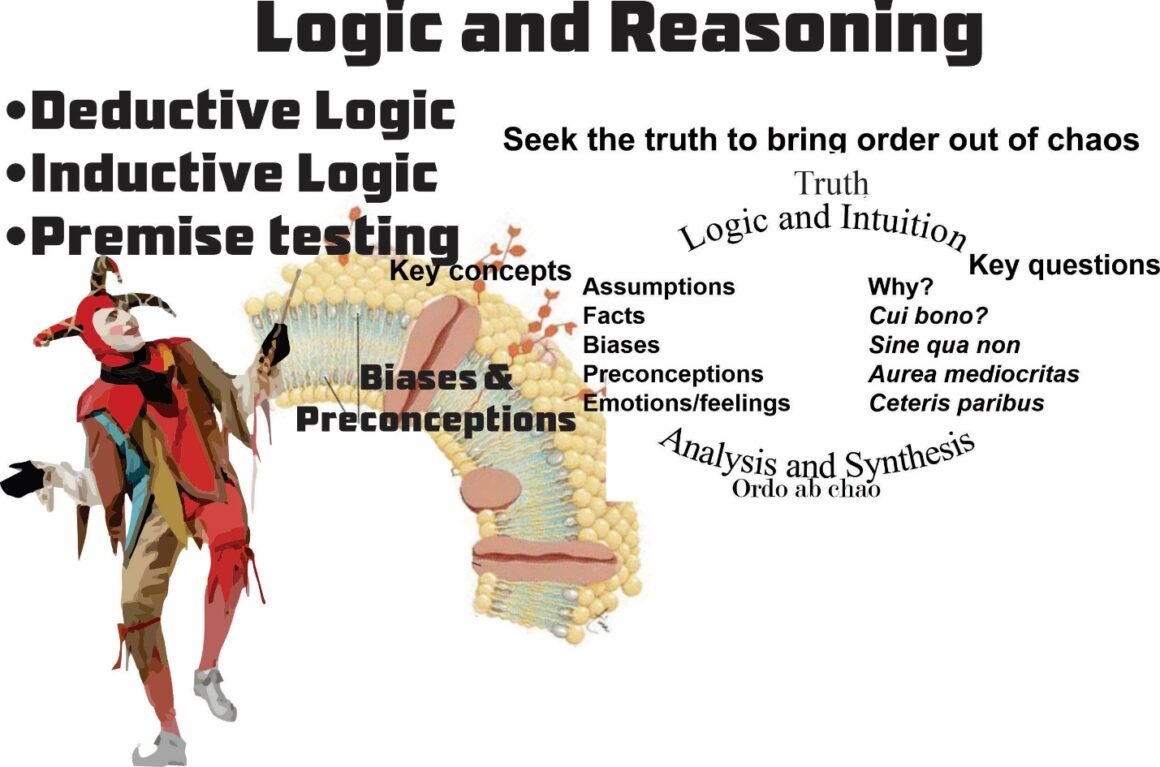

Logic and reasoning are two key components of system 2 thinking. Logic is developing the deductive syllogisms or inductive logic. Reasoning is testing the major and minor premises to ensure they are valid. To help understand this process, consider the two deductive syllogisms in the table below.

| Syllogism Elements | Security | Fairness and Stability |

| Major Premise | Creating the conditions for overthrow or destruction of the Constitution and the Republic is treason. | Income and social inequality promote instability and can threaten the Republic. |

| Minor Premise | Government policies create the conditions for the destruction of the Constitution and threaten the Republic. | Government programs reduce income and social inequality. |

| Conclusion | Government officials are guilty of treason. | Government officials promote the safety and stability of the Republic and Constitution. |

The two deductive syllogisms are both logically valid, but they are contradictory. The way our political system seems to work now, both sides accept their syllogism as valid and the other as false. But policy makers and analysts and voters need to go beyond simply taking them and other issues at face value and dig into them. The situation is further complicated because advocates rarely show the issues as logical syllogisms like those in the table. Rather, many advocates seek to clothe their complex issues in hundreds, if not thousands, of pages. Consider the Affordable Care Act and the statement, “we need to pass it to determine what it is.” I don’t care what side of the political divide you are on. This is scary. And it is not an isolated example.

Minor premises can have many clauses. My plebe Logic and Composition instructor demonstrated this when he showed us Jefferson organized the Declaration of Independence as a deductive syllogism. The major premise is that if a government does not take care of the people, the people have a right to replace it. Jefferson lists the grievances and issues which are a series of minor premises to show the conditions of the major premise are met. Then, he concludes American colonies should be independent.

So with this example, let us look at the two deductive syllogisms above. The goal is not to show one is right, and the other is wrong, but to explore the questions and issues to ask to determine the validity of the major and minor premises.

| Premise | Security | Fairness and Stability |

| Major |

|

|

| Minor |

|

|

From a macro perspective, we need to understand our biases. As we look at evidence to evaluate the questions above, our biases tend to color or analysis or even exclude pieces of evidence that do not fit our expectations. This represented by the membrane in the opening figure. The more permeable the membrane—the better that we understand our biases and preconceptions—the more data that passes through it. But even with more data passing through the membrane, we still need to take care that biases and preconceptions do not color how we process the data and turn it into information.

That is, I suspect, the fundamental problem in reconciling the two deductive syllogisms. Both sides have significant biases and preconceptions and are blind to the merits of the other side’s argument. These conflicting biases have risen to such a high level that meaningful dialog is all but gone from politics and policy. Responsible citizens need to engage in critical thinking and restore dialog rather than one-way discourse.