The Tragedy of the Commons: The Political Commons

I first came across the problem (tragedy) of the commons in a political science course in grad school. We read a remarkable work by Elinor Ostrom about the problem. Her work both resonated with me and left me looking for more. I thought the problem was bigger than the competition for natural resources.

So, what is the tragedy of the commons? Alexandra Spiliakos, in the Harvard Business School Online, wrote:

The tragedy of the commons refers to a situation in which individuals with access to a public resource (also called a common) act in their own interest and, in doing so, ultimately deplete the resource.

This economic theory was first conceptualized in 1833 by British writer William Forster Lloyd. In 1968, the term “tragedy of the commons” was used for the first time by Garret Hardin in Science Magazine.

This theory explains individuals’ tendency to make decisions based on their personal needs, regardless of the negative impact it may have on others. In some cases, an individual’s belief that others won’t act in the best interest of the group can lead them to justify selfish behavior. Potential overuse of a common-pool resource—hybrid between a public and private good—can also influence individuals to act with their short-term interest in mind, resulting in the use of an unsustainable product and disregard the harm it could cause to the environment or general public.

Ostrom identified eight “design principles” of stable local common pool resource management:

- Clearly defining the group boundaries (and effective exclusion of external un-entitled parties) and the contents of the common pool resource;

- The appropriation and provision of common resources that are adapted to local conditions;

- Collective-choice arrangements that allow most resource appropriators to participate in the decision-making process;

- Effective monitoring by monitors who are part of or accountable to the appropriators;

- A scale of graduated sanctions for resource appropriators who violate community rules;

- Mechanisms of conflict resolution that are cheap and of easy access;

- Self-determination of the community recognized by higher-level authorities; and

- In the case of larger common-pool resources, organization in the form of multiple layers of nested enterprises, with small local CPRs at the base level.

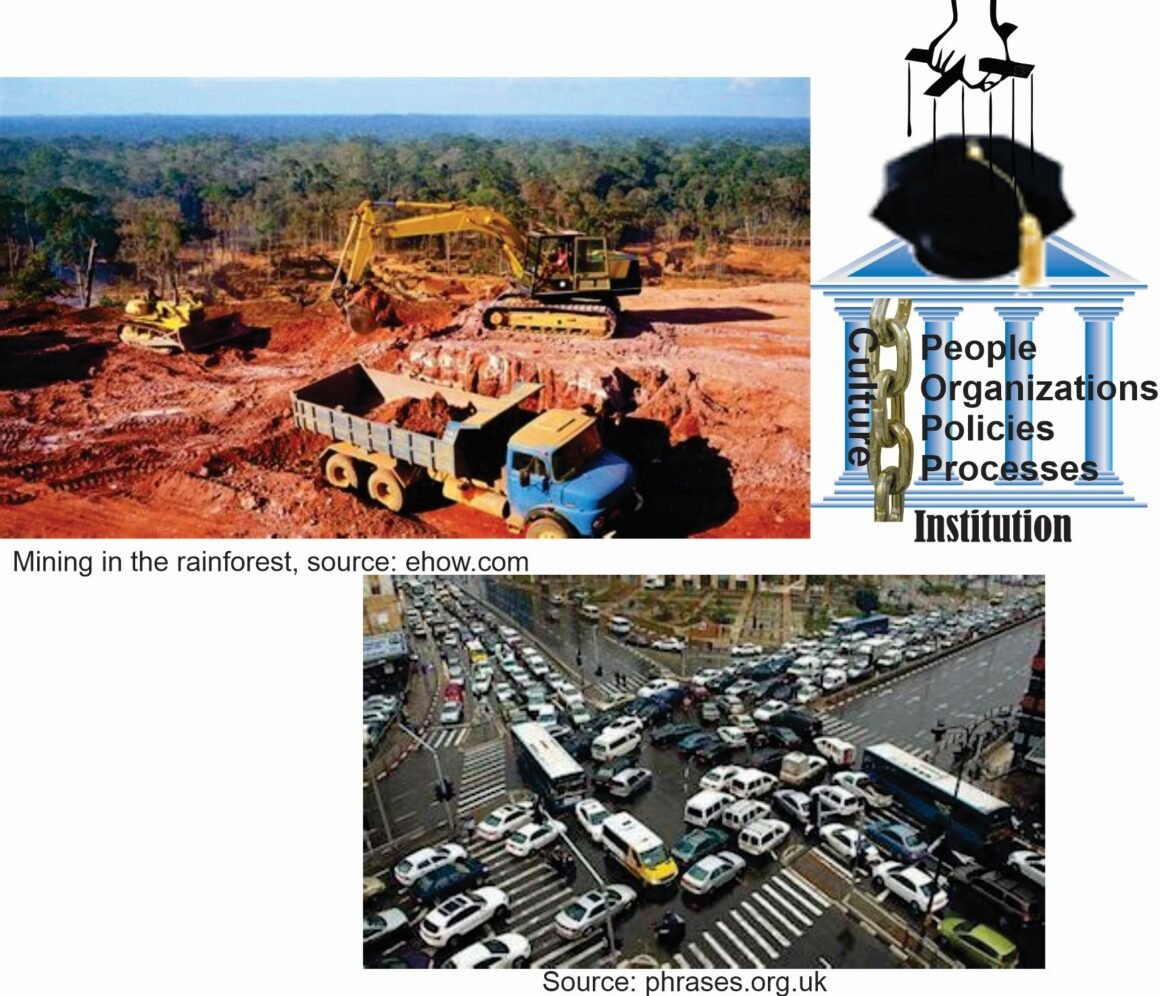

Most research on the commons deals with natural resources, such as the rainforest in the top image. Some recent scholarship now looks at the digital domain. While this is a good start, it is only a start. There are bigger public issues than the digital domain, although the digital domain is a key enabler of all of them. I would like to add:

- Key transportation networks and routes. In the US, this problem is associated with heavy traffic, gridlock, and public transportation issues. Globally, the issue includes access to key sea lines of communication (SLOC) and airspace. Who has access to them and who controls them? When a government sets up toll roads, it restricts access to only those that can afford to/want to pay the toll? Who is entitled to access and who is unentitled, per Ostrom’s first principle? If a government can restrict access/entitlement based on economic status for this class of resources, can it do so for others?

- Healthcare. Is healthcare a fundamental right to which everyone is entitled? If so, are there limits on entitlements, such as all people are entitled to basic lifesaving care, but not to plastic surgery? Is everyone entitled to Narcan, even if the overdose is because of their own actions? Is body shaming wrong or can it help reduce obesity and the associated health problems and expense? Can one’s action eliminate an entitlement?

- Education. This is a complex and critical commons. Education is vital to a healthy republic, especially in a complex and changing world. Citizens need the skills to assess information and make effective decisions in the ballot box. Yet the US education system is failing. Our education is barely in the top 30 in the world and is falling rather than recovering. From a commons perspective, there are a few key questions. What do we teach and who decides it? What is the role of the states, the schools, and parents in education? Who pays for it? The last question seems simple: the government. Yet local taxes fund many schools, setting up potentially unequal systems. Should parents have the right to send their children to the best school—private or public—regardless of location?

- Children. For most of US history, parents had the responsibility to raise children. Now, starting with Hillary Clinton’s “it takes a village to raise a child” some elements of society think the state has responsibility to raise children. Washington state recently stated they would take children from parents if they forbade their child from gender reassignment surgery. I sat in a Virginia Board of Education meeting that discussed this issue. There were many speakers that said parents should have limited or no role. Who should be responsible for raising children? Another key issue is discipline. Should parents be able to spank their children? Starting with Dr. Spock, discipline became a social matter. The situation is becoming like Huxley’s Brave New World. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? What are the entitlements and enforcement issues at stake?

- Government programs and policies. This is perhaps the biggest commons of all and continues to grow as the government expands. On the surface, politicians and bureaucrats control government programs and policies. Yet, the electorate votes in the politicians. Social justice advocates state the voting qualifications are racist and the Constitution that frames them is as well. Originally, only white male property owners could vote. Yet this set of qualifications is not in the Constitution. The Constitution left voting up to the states. What is interesting is the amendments to the Constitution that provide for voting rights all extend the franchise.

The key difference between the standard issue of the commons and these new areas is governance and a different definition of “resource”. In the traditional definition of the commons, they are essentially ungoverned, and no single government controls them. In these new areas, the government controls them, but who controls the government and drives the policies that set access rules?

Some related theories to manage the commons:

- Rational Actor/Choice Theory. This theory states that people make decisions to maximize their utility. It has come under some criticism that people may maximize utility in the short run at the expense of long-term utility. Are people rational? Jonathan Haidt, in The Righteous Mind, argues they may not be. Can Ostrom’s model work if the people are not truly rational?

- Game Theory. Game theory helps to predict the choices rational actors make in contested situations. Theory is useful in many situations, but what happens when emotions take charge of rationality?

- Agency Theory. Politicians and bureaucrats are agents of the electorate. Likewise, corporate CEOs other organizational leaders, such as union leaders, work as agents for shareholders and members. In theory, the agents execute the will of those they represent. But what happens if the agents have a will of their own and no longer feel accountable to those represent?

Follow on pieces will take Ostrom’s model, along with the three theories above, to develop a tool to assess the governance of the political commons. Our disputes over the political commons and a way ahead are potentially more divisive and dangerous than over slavery. Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution (repealed by the 13th Amendment) was a compromise to keep slavery. While the focus was on 3/5ths denigrating the humanity of slaves, the actual intent was to limit the power and representation of slave states. We need to understand our history and how it affects today. Education is perhaps the core political commons area.