Why do we act in other than our self-interest? Is the rational actor/choice theory valid?

Over a few blog entries (see the Defending the Republic series), I have wondered why people who do not seem to benefit from social justice efforts support and endorse them. Why would a white male push an agenda designed to deny his rights? Why do companies embrace the Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) agenda when it potentially makes them less competitive through lowered standards, higher costs, and policies that prevent talent from reaching its highest state?

Many political scientists used to assume that people vote selfishly, choosing the candidate or policy that will benefit them the most. But decades of research on public opinion have led to the conclusion that self-interest is a weak predictor of policy preferences. Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind (p. 100). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

If the premise of the book, and specifically the quote above, is true, it shoots holes in the rational actor/choice theory. Haidt posits people do not respond so much as rationally, but to maintain social standing and connections. He wrote:

Rather, people care about their groups, whether those be racial, regional, religious, or political. The political scientist Don Kinder summarizes the findings like this: “In matters of public opinion, citizens seem to ask themselves not ‘What’s in it for me?’ but rather ‘What’s in it for my group?’ ”

Political opinions function as “badges of social membership.” Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind (p. 100). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

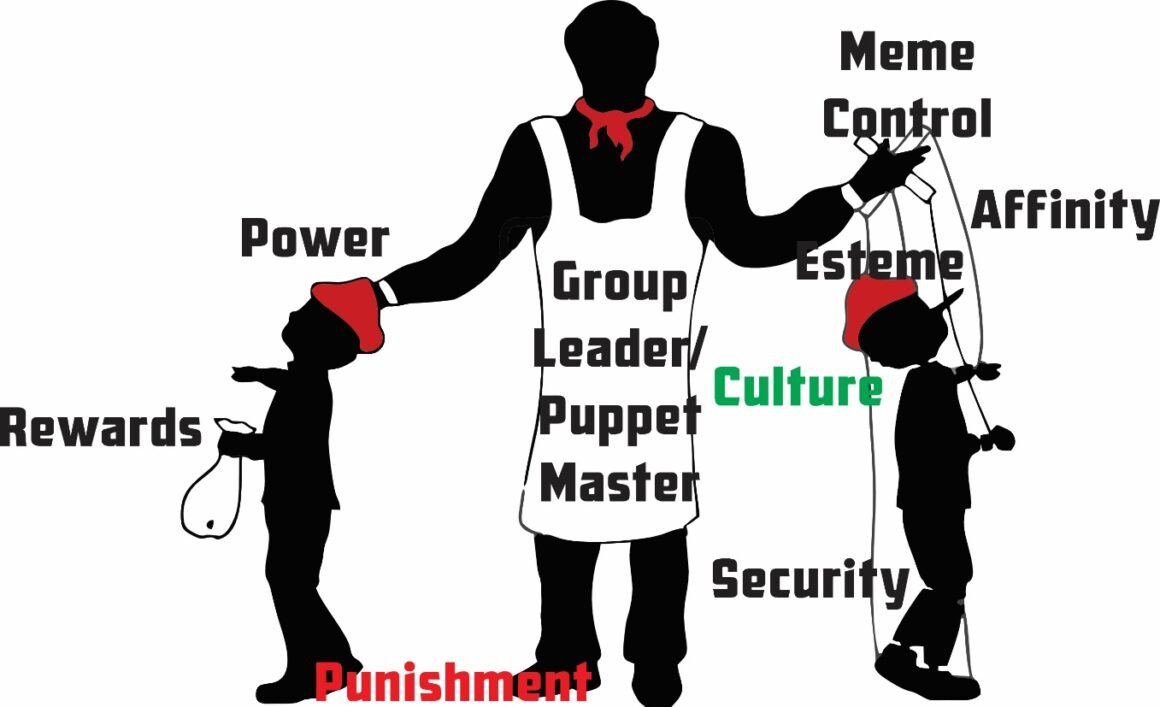

While I don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water regarding rational actors, Haidt and Kinder seem to think that groups carry more clout than self-interest. For individual group members, they may be right. But for the group leaders, I suspect they are wrong and work according to rational choice theory. Their rational choice is to manipulate the group members for money and profit.

This is perhaps prevalent in social justice, for example, see the case of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) leader using contributions to buy houses and race-based advocates such as Al Sharpton that owe large amounts of back taxes and have made fortunes. But it is also present in other groups. Look at the televangelists, such as Jimmy Swaggart, who have used donations to grow their personal wealth and power. I suspect it may also hold for groups that advocate for diseases and other special causes. Not a few people believe cancer, diabetes and other diseases would be cured by now if the American Cancer Society and other groups did not make so much money off the disease. We also see the same thing in the government bureaucracy, where it is almost impossible to kill off government programs, regardless of whether the problem is resolved or the program makes the problem worse. These leaders are all rational actors, making decisions that benefit them. Although what happens to group members is often a different story.

We see the same with social influencers on social media. Whether it be social justice narratives, food and beverages or toys, the influencers make their living by telling people what to do and what to buy. They create and propagate memes to shape people’s attitudes and actions.

Now look at unions, especially the various teachers’ unions. Are they making education better? International ratings argue they do not. America continues to slide in global education rankings.

So why do the group members stay in the group? Some are true believers, some like the acclaim and power they get from the group, and some are too afraid to challenge the group leaders and their agenda. Look what happens to college professors, even tenured ones, when they challenge the social justice agenda. They get fired. And this happens in corporations and elsewhere. It is almost like the Roman Catholic church and the Inquisition. Torquemada is alive and well in these social justice groups. They all get something out of the arrangement, so they may have a modicum of a rational choice. But Haidt would say it is not a rational choice per se, but the rider working with the elephant. Haidt would say this is less a rational act by classic definitions and more of an act to justify the elephant’s appetites and directions.

But the power-brokers make rational choices. The rational choice theory is not so much wrong as perhaps misapplied. So, what is in a name? Perhaps we need to tie rationality to the situation and the person to understand it.