Virtue-based Leadership, Part 4: Virtue, Morality, and Ethics

Abstract: While there are similarities and crossovers between morality, ethics, and virtue, they are not the same. For me, at least, morality is essentially based on operant conditioning—reward and punishment. Ethics are based on rules and systems. Both are mutable and will vary. Virtue, however, is immutable. That is why virtue is harder to enact and sustain, but more reliable for a leader. Those that base conduct on ethics and morality may be bought by strong rewards or punishments or different ethical systems that may justify different behavior. Perhaps we need to approach the issue from both the top and the bottom of an organization and be an example of virtue and strong leadership. The leader needs to understand the people in the organization, its culture, the way it operates, and its core values. If it does not have core values that are widely accepted, that may be a fundamental problem. The leader must set the virtue example in everything he or she does. Virtue is its own reward.

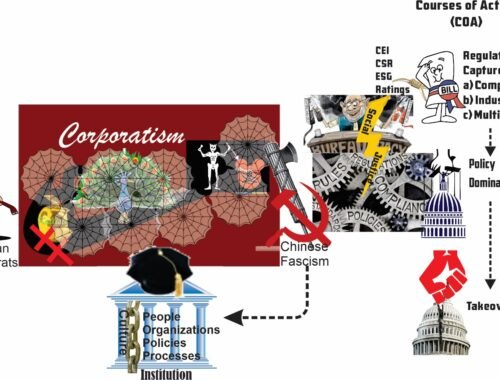

My call sign in Bosnia and Afghanistan was Paladin. One of the interesting aspects of non-standard units and communication systems was the ability to select call signs. For me, the Paladin is a symbol of virtue. The Free Dictionary says a Paladín is “1. A paragon of chivalry; a heroic champion. 2. A strong supporter or defender of a cause: “the paladin of plain speaking” (Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.). 3. Any of the 12 peers of Charlemagne’s court.”

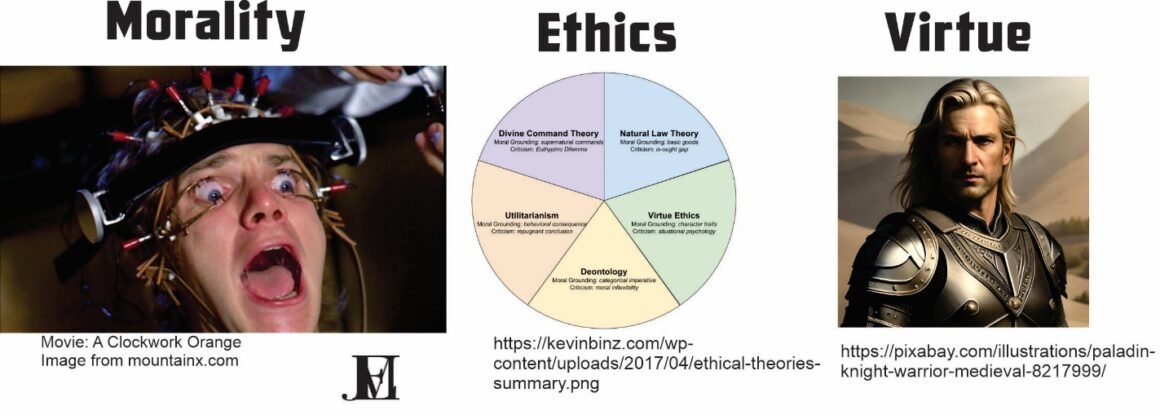

My fascination with the Paladin goes back to high school, where my character in D&D was a Paladin and my reading of The Song of Roland. Roland was one of Charlemagne’s paladins and the song is about Roland covering Charlemagne’s retreat through the Pyrenees. It is a story of sacrifice and heroism. And Charlemagne was one of the major forces that wrested Europe from the Dark Ages. For me, the Paladin is a symbol of virtue and virtuous leadership. The right picture above under virtue is a Paladin.

The left picture is from A Clockwork Orange, where the state used operant conditioning (see Operant Conditioning, Path Dependency and Societal Revolution, Part 1) to change behavior. The middle picture shows different systems of ethics. While there are similarities and crossovers between morality, ethics, and virtue, they are not the same.

Given the potential variability of morality and ethics, virtue is the optimal, but most difficult approach.

Morality was once almost a given in the west. But as I discussed in Virtue Wherefore Art Thou, as the power of religion wans, so does the consistency of morality. I say consistency because new concepts arose to replace religion, potentially creating new moral codes, but they often pit one group against another. Therefore, they are not virtuous. In the end, morality is based on operant conditioning’s system of rewards and punishments. In some circles, operant conditioning is a major part of behavior modification therapy. In my opinion, any system that relies on reward and punishment is susceptible to failure and people leaving it for a better set of rewards. Telling someone low on any of the moral development models or Maslow’s hierarchy that virtue is its own reward may not be very successful. A leader needs to understand the strengths and weaknesses of such an approach and work to bring the organization members to a higher state of awareness.

Most ethical systems seem to be more academic than practical. Utilitarianism reads well, but its implementation is difficult. In most work situations, how can leaders and team members practically calculate utility? Rule utilitarianism helps a bit with certain steadfast rules, but is still difficult in practice and if the rules are too constraining it defaults to the moral code and operant conditioning if it has punishments to enforce the rules. Perhaps the best way is some economic analysis. But if we are not careful, we wind up with the Ford Pinto situation discussed in Part 2 of this series. Of the various ethical systems, perhaps the duty oriented deontology is the closest to virtue, and the best suited to operating organizations. Of these systems, perhaps the most workable is Kant, particularly his categorical imperative. He formulated three versions of the categorical imperative, two of which are the most relevant: what happens if your actions are universalized and treat others as ends in themselves and not means to an end? These two formulations can readily guide and govern organizational behavior.

From a virtue perspective, Kant is my guiding principle. Virtue, for me, is about doing the right thing, for the right reasons, without hope of reward or fear of punishment. It is also related to duty, which, as Robert E. Lee wrote, “Duty, then is the sublimest word in our language. Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more; you should never wish to do less.”.

So what is a leader to do in a modern organization with conflicting societal values and mores?

The traditional western values are in a state of flux, what is constant? How does a leader establish a virtuous culture if people do not agree on values, mores, and concepts?

Perhaps we need to approach the issue from both the top and the bottom and live leadership. The leader needs to understand the people in the organization, its culture, the way it operates, and its core values. If it does not have core values that are widely accepted, that may be a fundamental problem.

Perhaps we need to approach the issue from both the top and the bottom and live leadership. The leader needs to understand the people in the organization, its culture, the way it operates, and its core values. If it does not have core values that are widely accepted, that may be a fundamental problem.

From the bottom, the organization has rules, policies, processes, and procedures, as well as culture. These inform the moral layer of the organization. This is where most people in the organization reside, so leaders better get it right. And they need to reduce or minimize the variable and uncertainty in organizational norms.

In the middle, do organization members have a sense of duty? I suppose that depends in part on the organization’s purpose and mission statement. Do people know and understand it? Is it well written and does it make sense or is it just a pablum (like many are)? We aim to be the best in the business is not a meaningful mission statement. Ethics, especially if it is based on duty, requires a clear understanding of the duty and of how it relates to the organization.

At the top, do members understand and practice virtue? Virtue leaders must both teach and exemplify virtue. As Erickson noted, this must be an ongoing practice. If the leader lets up or acts in a non-virtuous manner, the problem will spread through the organization like a plague.

Part 5, the last installment in this series, will look at practicing virtue.