Culture and Strategy: A Match not a Competition

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” – various, possibly Peter Drucker.

“It must be considered that there is nothing more difficult to carry out nor more doubtful of success nor more dangerous to handle than to initiate a new order of things; for the reformer has enemies in all those who profit by the old order, and only lukewarm defenders in all those who would profit by the new order; this lukewarmness arising partly from the incredulity of mankind who does not truly believe in anything new until they actually have experience of it.” Niccolò Machiavelli.

The quote from Machiavelli seems to reinforce the statement from Drucker. A change in strategy requires organizational change, is risky and many will not support it, unless the culture also changes, which can be difficult.

But I do not think the relationship between strategy and culture is that simple. Rather, it is more like a family having breakfast together. Strategy and culture are like parents. When the parents work together, the family normally does well—at least when they work for the family’s benefit and prosperity. In large families, there can be various agendas that may compete with or even conflict with the parents’ agenda. Now that is not all bad. Conflict, at least when it is open and constructive. Constructive conflict can lead to problem solving. Mary Parker Follett, in Constructive Conflict, has some excellent thoughts on the topic. For example, she wrote:

Thus we shall not be afraid of conflict, but shall recognize that there is a destructive way of dealing with such moments and a constructive way. Conflict as the moment of the appearing and focusing of difference may be a sign of health, a prophecy of progress. Compromise does not create, it deals with what already exists; integration creates something new….

Strategy needs to recognize conflict will happen and where and why. Culture needs to bring it in the open and keep it positive as Follet discusses in her work.

Especially in large organizations, there can be different culture, or perhaps different facets of culture. For example, the culture in an infantry battalion differs from the culture in a transportation battalion. Yet, they both work together to enable the overall strategy and mission accomplishment and share core aspects of the Army culture.

The same effects happen in non-military organizations. For example, the sales team has a different culture than the delivery team, which has a different culture than the finance team. In a defense contractor, particularly when defense is not the core line of business, the retired military employees have ties to the military customer and can compete with their ties to their employer. The contractor expects financial results and while the retired military understands that, they also understand the customer has pressures and dynamics the non-military in the contract may not understand or even realize. The retired military needs to balance the loyalty to the military and the loyalty to the contractor. A successful strategy will recognize this and leverage it for better customer service and long-term financial success.

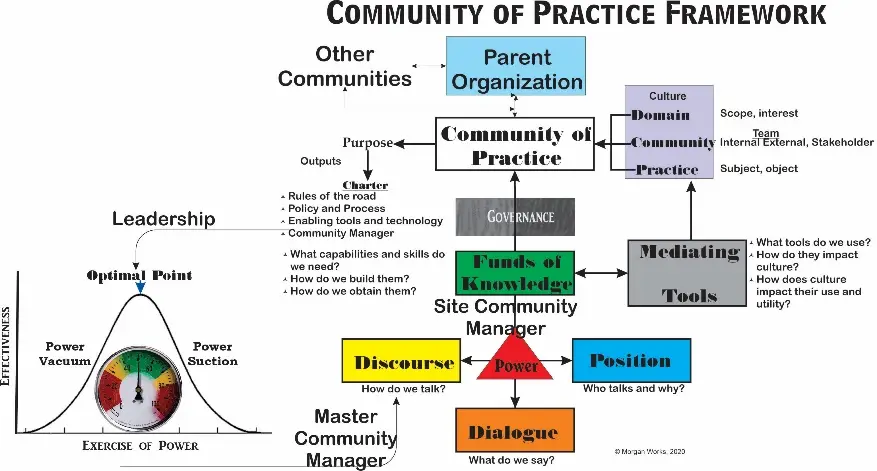

One solution to bridge strategy and culture is to develop robust communities of practice (COP). The keys to an effective COP are open communication, trust, dialog, and tight integration with strategic, operational, and tactical plans.

One solution to bridge strategy and culture is to develop robust communities of practice (COP). The keys to an effective COP are open communication, trust, dialog, and tight integration with strategic, operational, and tactical plans.

Leaders need to give the COP a task and purpose, appoint a Master Community Manager, and approve the governance documents. As needs arise, they should ask the for information, advice, and to solve problems.

The Master Community Manager oversees all COPs and ensures that each COP has an effective COP Manager, approved governance, and meets the needs of the organization. The Master COP Manager needs to find an optimal point for each COP of leader presence and the management of discourse and dialog.

The COP Manager needs to understand what knowledge and skills each member brings, especially non-documented skills. This is known as Funds of Knowledge in a classroom, but has direct applicability to other organizations. For example, a team member may have once worked in accounting, but now works in another department. Those accounting skills are still relevant. The manager must also monitor discussion and dialog and ask questions to stimulate the discussion. Too often, a COP starts out strong and members are excited, but over time, this excitement dries up if the COP does not continue to have a strong and relevant purpose that is clearly tied to strategy, operations, and tactics.

There will be conflict and differing ideas. A well-run COP is a good place to bring the conflict into the open and ensure it is constructive rather than destructive.