Corporatism Part 2: The Web of Influence and Power

The Symbiosis of Power and Influence

“The price good men pay for indifference to public affairs is to be ruled by evil men.” Plato

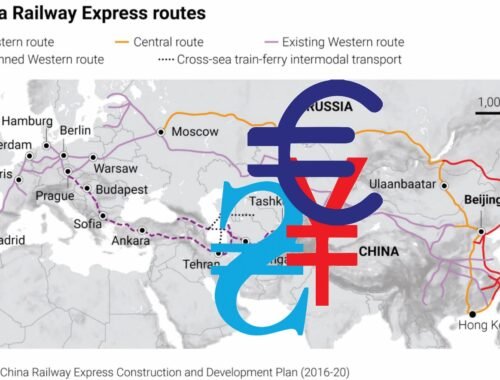

Part 1 developed the concept of a web of influence and power, as shown in Figure 1. Part 2 expands upon this concept to analyze the web and to lay the foundations for an assessment of its effects.

Figure 2 The Symbiosis of Power and Influence

“Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. The friend of popular governments, never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice. He will not fail therefore to set a due value on any plan which, without violating the principles to which he is attached, provides a proper cure for it. The instability, injustice and confusion introduced into the public councils, have in truth been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have every where perished; as they continue to be the favorite and fruitful topics from which the adversaries to liberty derive their most specious declamations.” James Madison, Federalist #10 (Madison, 1787)

Power and influence have a symbiotic relationship. Influence shapes and generates power, and power gathers influence. While the relationship seems like a chicken and egg question. Which comes first? It may not. In a democracy, campaigns and elections shape much of the influence and power relationships, specifically by funding them. People with wealth create corporate entities designed to provide funding. Once the process starts, it creates a feedback loop where both power and influence grow stronger. But it is the deliberate act to create the corporate entity that starts the process.

Madison hoped that “a more perfect union” would prevent this process. Unfortunately, he was wrong. Factions arise naturally as people with like interests band together to influence policy development and government activities such as taxation, spending, regulation, and programs. This is the chicken the lays the egg. These naturally emerging factions create the egg that keeps on giving.

Madison thought a large republic would provide the variety of interests with an involved electorate. While he and other founders were prescient in so many areas, he was wrong in this one for a few reasons.

- The original electorate was landowners. This concept was not so much racist and sexist as modern activists would have us believe. Rather, these were the people that paid the taxes to pay for the government. With the several constitutional amendments that extended voting to all citizens over eighteen (14th, 15th, 19th, 24th, 26th), this concept changed. We now have a large body of citizens that pay little or no taxes, yet vote on representatives that control taxation and spending policies.

- The 16th Amendment fundamentally changed congresses ability to raise taxes and freely spend them. Prior to this amendment, there was no income tax and the Constitution constrained how congress could spend.

- The 17th Amendment fundamentally changed the senate. Prior to the amendment, states appointed senators and the senators represented the state. After the amendment, senators were popularly elected, providing for an even larger web of power and influence powered by electoral contributions.

This is not to say that universal suffrage or a change in the senate were bad decisions. The intent is to show the changes significantly altered the calculus that drove some of the founders’ concepts and ideas. Therefore, we must account for the changes in managing the web of power and influence.

With these three factors that constrain the effects of Madison’s concept, is there a way to control these chickens? Some of the research on pluralism and corporatism tries to lay out why this relationship happens and how to manage it. I suspect these groups rely upon an uninformed and disinterested electorate that either does not vote or is easily swayed. The cure is an educated and informed electorate.

This requires an effective education system that educates rather than indoctrinates and a free media that provides information rather than editorial sound bites. This may require a rebuild of the education system and a look at the media as trusts, and potential trust-busting the way Theodore Roosevelt did in the early 20th century. That is the only way Madison’s vision in Federalist 10 will come to fruition. Let us set education and information aside for a moment and focus on something the founders did not spend a great deal of time on, regulation.

The Web and Government Regulation

Government regulation became progressively more important after the American Civil War. With a developing industrial economy and changing workforce as people moved away from agriculture to the factory, interest groups advocated for better working conditions, safety, and some form of control over large corporations. Books such as Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906) helped to propel this movement. Theodore Roosevelt

First, as a conservationist, he used the power of the new bureaucracy and his inherent powers as president to create wildlife reserves and federal parks. While a fine and laudable aim, it created federal sites on state land and set the precedent for increasing federal programs and encroachment on the states. Second, he used federal law successfully to bust trusts and large monopolies that he deemed antithetical to the public good. While Congress passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890) years before Roosevelt, it was little used and ineffective. Roosevelt’s dynamism and energy brought life to the act. His trust busting set the stage for larger federal regulation and oversight.

Government regulation and oversight should break or reduce the web of power and influence. Bruce Lloyd, in How do Governments add value to society? What are governments for?, states:

“A core dimension of the evolution of governmental and political/democratic systems in the past – and today – has been to attempt to reduce ‘abuses of power’ that would otherwise occur within any totally unregulated society. As a result, policies need to focus on, and be evaluated against, a ‘restricting the abuse of power’ agenda.” (Lloyd, 2021).

Figure 3 Regulatory Affairs and Power

Madison (or Hamilton) in Federalist #51 wrote, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” (Madison, 1788). The same may be said for corporate entities. Neither men nor corporate entities are angels and abuse of power emerged and government regulation arose to reduce the abuse of power.

While Lloyd’s statement is true, it is only half of the equation. As governments build regulatory bodies, they accrue power. With the web of influence, this power spreads and grows. Effective governments balance the need to regulate potential abuse of power from corporate sources, with the potential abuse of power from the government and the secondary sources of corporate power and influence government policy and action creates. Lloyd notes this issue, and does, however, caution:

“Unfortunately, all too often the processes of government can themselves easily end up also being responsible for abuses by becoming self-serving. Hence it is vitally important to have effective accountability, within whatever government structures are in operation.”

Effective policy must take this balance into account. Otherwise, the cure can be worse than the disease. The “owner operators” of the Republic need the education and information to understand complex issues and hold their representatives accountable for effective policy.

The Web and Leaders

“The measure of a man is what he does with power.”

Plato

When I was younger, I naively rebelled at Lord Acton’s statement, “power corrupts, power corrupts absolutely.” I also rebelled at the esoteric literature’s admonition that you must slay the ego. The two are very much related. The ego whispers to us that we can use power without being corrupted.

Figure 4 The Temptation of Power and Influence

J. R. R. Tolkien had amazing insight into the human condition. In the Lord of the Rings, there were two instances that depicted the interaction with power. The first is when Frodo offered the ring to Galadriel.

Frodo: If you ask it of me, I will give you the One Ring.

Galadriel: You offer it to me freely? I do not deny that my heart has greatly desired this. In place of a Dark Lord you would have a Queen. Not dark but beautiful and terrible as the Morning. Treacherous as the Sea. Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair.

Galadriel: I pass the test. I will diminish and go into the West, and remain Galadriel.

The second instance was when Frodo came under Faramir’s power and Faramir did not take advantage of it. The movie kept Galadriel’s response, but made Faramir fall under the spell of power. I’m not sure why the movie’s script writer elected to change Faramir, but left Galadriel more or less intact.

The web of power and influence is a source of power and it can readily corrupt the people that use it. How do we rise above this temptation? How do we identify those seduced by it?

The conundrum is we need to wield power to effect change, yet not be seduced by it. That is where the esoteric admonition to slay the ego kicks in. The ego is critical as it is what delineates the self from everything else. Yet if we cannot keep the ego in check, it gets seduced by the power it must use to create the changes it sees must occur. The more power it wields, the greater the temptation to think we can rise above Lord Acton’s warning, because we are good and what we seek to create is good. If we cannot divorce the ego from the use of power, we get seduced from it.

Weak leaders are readily seduced by the siren call of power and will adapt and morph their values like a chameleon to suckle its hypnotic nectar. In time, they lose virtually every attribute associated with leadership. That, I suspect, is why the slave whispered to the Roman General during a Triumph that all glory is fleeting. It leaves the weak leader and leaves him or her a slave to finding that glory and getting another hit of power.

Strong leaders understand the siren’s call and nurture other leaders so they can share the power to accomplish organizational goals. They do this for the love of the organization and its values.

Figure 5 Washington Resigning His Commission

Figure 5 depicts on the most important events in American history, Washington resigning his commission. His love for Mount Vernon transcended a desire for power. He used the Roman story of Cincinnatus, who walked away from power to return to his lands, to create the Society of the Cincinnatus to help others make this decision.

Jefferson was similar. He advocated a simple, agrarian life as opposed to Hamilton and others. He could have channeled his intellect and reputation to achieve commercial wealth and success, but didn’t.

With Washington and Jefferson, however, their love blinded them to another problem, slavery. I suspect both understood it was wrong, but could not reconcile that understanding with the operation of their plantations.

Now, look at Ben Franklin. Like Jefferson, he could have translated his intellect and reputation into tremendous commercial success. But he didn’t. He devoted his life’s efforts to the founding of the Republic. He was an amazing person.

I suspect we need to be careful of the power of love as well as power. A study of Franklin may be rewarding. Although Washington and Jefferson had a tremendous flaw, it should not blind us to the critical service they provided and their ability to resist the siren call of power.

The common denominator between them and the other founders of the Republic was a common vision of success and a dogged determination to achieve it.

Strong leaders help to define and communicate values and set a culture that sustains them.

Setting A Vision of Success

Organizations and governments must clearly define success, to include the measure needed to accomplish success and the metrics to assess it. Values need to underpin and shape these criteria. Success should be based on securing and sustaining values.

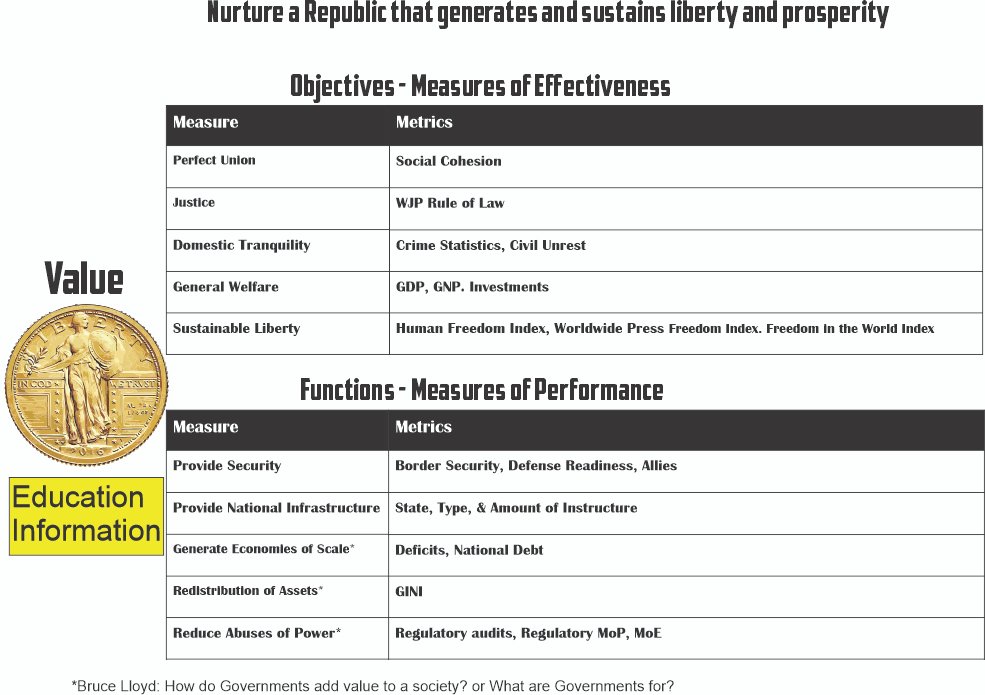

Lloyd (2021) asks two important questions: how governments add value? And what are they for? He raises three government functions to add value, but I’m not sure he defines “value”. The Preamble to the Constitution, at least for the US, answers the value question with the five objectives it lists for the Constitution. Lloyd’s three functions could work to produce the 5 elements of value.

Figure 6 shows the functions and objectives based on the Preamble. They include Lloyd’s three functions as well as two others: provide security and a national infrastructure.

However, the functions and objectives do not really answer the question of what is success? If we go back to the Preamble, it clearly states to ensure the blessings of liberty for ourselves and posterity. Therefore, perhaps the definition of success is a Republic that generates and sustains liberty and prosperity.

potentially rate fairly high. Now I’m sure that’s not Lloyd’s intention, but I am concerned we have too much emphasis on Measures of Performance (MoP), which measure whether we are working the functions and not enough on Measures of Effectiveness (MoE), which measure whether we are achieving what we intended and Measures of Success (MoS), which measure whether we are achieving and sustaining success.

Figure 6 Measure and Metrics for Government Value

We often, especially looking at government, seem to devolve to the simplest way of looking at the situation. For example, let us look at the redistribution of assets measure for a moment. What is better to be a poor country with a near perfect distribution of assets, but low standard of living or a wealthy country with a high standard of living for all, but a less evenly distribution of assets? I don’t think this is a moot question, because there are those that think a level distribution of assets is a superior public good. But having said that, a poor distribution of assets, even when all have a high standard of living can (and will) spark jealousy and social instability.

Figure 6 includes metrics for the MoPs and MoEs. The gold box under values shows Education and Information. They are critical to generating and sustaining prosperity and libery. A Republic depends on an educated and informed electorate that can elect responsible represenative. The electorate needs to be able to critically assess issues and make informed decisions. “Owner-operators” of the Republic must have objective measures and metrics to evaluate the performance of our government and our representatives’ performance.

Education and access to reliable information must also be measured and assessed. Are these government functions and, if so, at what level? Or are they private functions with governmental oversight/regulation?

Bibliography

Lloyd, B. (2021). How do Governments add value to society? or What are Governments for?, Academia Letters, Article 1208. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL1208.

Madison, James. Federalist No.10, Library of Congress website, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-1-10. (Originally published in the New York Packet, November 23, 1787.)

Madison, James (Or Hamilton, Alexander). Federalist No.51, Library of Congress website, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-51-60. (Originally published in the New York Packet, February 8, 1788.)