Diversification is a standard tool to reduce portfolio risk in finance. To do this, the portfolio manager seeks stocks with different risk profiles and potentially even industries and countries. But the managers do not just pick any old stocks. The stocks must meet their investment objectives and provide a targeted return on investment.

Diversification in a society or organization is like portfolio management. Societies and organizations seek diversity to engender new ideas and approaches. But they also seek diversification if the society is heterogenous. However, diversification in society is still about risk management. Diversification is ultimately about giving all members in society equity (see The E in DIE) and thus ensuring domestic tranquility. Organizations eventually echo the society in which they are immersed, especially when the government compels it and powerful groups in society push for it, sometimes even violently. There are clearly those in the movement that seek the ownership aspects of equity without earning them.

Popular Stories Right now The social justice movement is squarely behind diversity. But they advocate surface diversity, based on external characteristics such as race and gender (whatever they think that is). However, there is little, if any, evidence that surface diversity has a positive impact on organizations.

Yves R. F. Guillaume, Jeremy F. Dawons, Steve A. Woods, Claudia A. Sacremento, and Michael A. West’s article Getting diversity at work to work: What we know and what we still don’t know, published in the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (2013), is a discussion of the limitations of research into the effects of diversity and whether it works. The authors cite various frameworks and their strengths and limitations, but the most interesting statement is evidence-based analysis is organizations’ fear of sharing their data limits meaningful research. The lack of data and the current climate surrounds it means researchers have a significant challenge of testing theoretical frameworks and draw valid conclusions that can be extended across organizations.

The article may be dated, but I suspect that the conclusions are still valid. Most other objective sources agree that perhaps the best case that can be made for diversity is deep or cognitive diversity. Deep diversity flies in the face of the social justice movement because it is not about race, gender, and other surface characteristics that the social justice movement treasures. Rather, it is about cognitive diversity—how people think and solve problems. The only objective evidence that diversity holds value is in cognitive diversity.

However, Both Pöyhönen and Baggio et al. found cognitive diversity is beneficial only in difficult and complex cases. Their studies were limited to single fields and, while unstated, seemed to be limited to System 2 decision-making. Further research may help to verify whether cognitive diversity helps to reduce biases that can impair System 1 type thinking (see Critical Thinking: System1 and System2 Thinking). It may also help to show whether cognitive diversity helps to build more reliable heuristics that are critical to System 1 thinking and decision-making.

Guillaume, et al. cite organizational culture as key to diversification efforts, but also need to consider organizations operated in a broader socio-cultural setting. Perhaps this broader setting needs to be more solution-focused than problem and legally focused to develop effective evidence-based frameworks that allow organizations to share data without fear of litigation and other blowback.

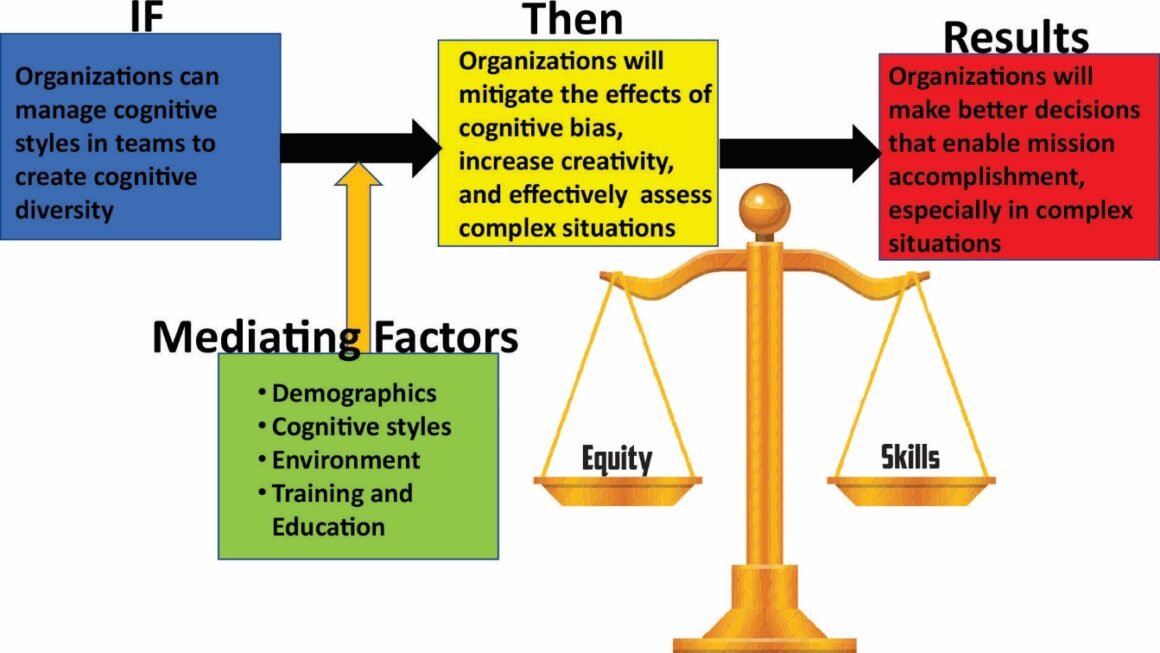

The opening figure is a proposed theory of change to investigate the effects of cognitive diversity. Appendix A has a Concept Map that provides more details on cognitive diversity and how it may work. This is a first step to evidence-based frameworks and includes

Research Questions

- How can we engage marginalized groups using cognitive diversity to help them take part in prosperity?

- How do organizations that implement surface diversity perform? Are there any benefits to organizational mission accomplishment?

- How can we best manage conflict within diverse organizations?

Supporting Materials

Deep versus surface diversity

Most sources differentiate between deep and surface diversity by distinguishing between demographic attributes (surface) and cognitive attributes (deep). For this study’s purposes, James Watson offers a perhaps more nuanced approach. It doesn’t disagree with the typical descriptions, but puts in the context of problem solving and decision-making.

Deep diversity concerns variables that exist at a level more nearly commensurate with the demands of the group’s task. Following Steiner (1972), task demands specify the resources that members must possess to complete their group assignment (e.g., their knowledge, skills, and abilities), as well as how those resources must be applied to achieve the best possible outcome.

Thus, deep diversity denotes differences among members that have at least the potential to affect group performance in a fairly direct way. By comparison, surface-level diversity typically refers to variables that are far removed from the specific demands of the group’s task. Therefore, surface-level diversity is usually assumed to affect group performance only indirectly, either through an association with some form of diversity at a deeper, task-relevant level, or through its (often negative) impact on the interpersonal dynamics of the group (Mannix & Neale, 2005; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). Watson (2007, p, 414)

Deep diversity is correlated to cognitive diversity. Following Watson and others in the deep diversity literature table in Annex B Additional Literature Review element: Deep Diversity, deep diversity facilitates group problem solving as long as organizations channel the potential conflict from the diversity into constructive venues.

Appendix A Concept Map

The Cognitive Diversity Concept Map shown in Figure 1 provides a mapping of the key concepts in the literature review and is discussed in Table 1 Literature Review Matrix. Thicker and solid lines show clear concept linkages supported by research. Thinner lines show concepts that are linked, but the research may not mention the concepts directly, such as Funds of Knowledge and Communities of Practice. Dotted lines show concepts that are linked according to some research, but the linkage is either disputed by other research or will need further research to confirm.

Appendix B Literature Review Matrix

Table 1 Literature Review Matrix

| Author/

Date |

Theoretical/

Conceptual

Framework |

Conclusions |

Implications for

Future Research |

Implications

For practice |

| How do organizations develop cognitive diversity? |

| Mello, A. L., & Rentsch, J. R. (2015) |

Provides a framework for how cognitive diversity may be achieved.

- Traits

- Developmental

- Acquired

- Exposed

|

“Although there is little overlap in the criterion variables across the studies of exposed cognitive diversity, it does appear that team member cognitions can be successfully manipulated and that manipulation in certain types of cognitions (e.g., perspectives, expectations) affects task process/behavior criteria, particularly those related to communication.” |

Analyze the impact of manipulation of various elements of the framework to determine their relative importance and the performance impact of the manipulation. |

The paper provides a framework for how cognitive diversity may be built and sustained in an organization |

| Bender, A., & Beller, S. (2016) |

“This overview focuses on three exemplary aspects of cognition: perception and categorization, number representation and counting, and explanatory frameworks and beliefs.”

These aspects seem to have much in common with the anthropological basis for Funds of Knowledge and Communities of Practice. |

Cultural tools and practices are key to understanding cognitive diversity. |

Future studies may look at these aspects of cognition and their cultural sources to align them with indicators of organizational success. Diversity for diversity’s sake could create more conflict than the organization can effectively handle or diffuse leader attention into areas that dissipate resources required for success. Clearly, cultural diversity is a success enabler, but research should show how it enables success for different organizations and at what point, too much cognitive diversity becomes a distracter. |

Culture is a key component. The anthropological basis of Communities of Practice and Funds of Knowledge may have key implications for effectively creating and employing cognitive diversity. Leaders must understand organizational culture and how it affects cognitive diversity and shape the culture to include more diverse perceptions that can enable organizational effectiveness. |

| Stoyanov, S., Jablokow, K., Rosas, S. R., Wopereis, I. G. J. H., & Kirschner, P. A. (2017) |

The paper uses the concept of Group Concept Mapping (GCM) and the Kirton Adaption-Innovation Inventory. |

“A-I theory states that simply being aware of differences in cognitive style is immediately helpful for managing diversity in groups. In addition, “bridgers” (in A-I terms i.e., team members–with intermediate scores relative to the current team profile) could help in managing the cognitive gaps in groups, provided these team members are motivated to do so and have the skills required” |

“It has been shown that cognitive diversity has a greater impact on decision-making than demographic diversity” (Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1999; Williams & Reilly, 1998). Likewise, cognitive style diversity is assumed to be a better predictor of team performance than traditional demographic variables (Miller, Burke, & Glick, 1998; Schilpzand & Martins, 2010).” Perhaps future research can look at how demographic diversity influences cognitive style. |

The cognitive styles in the paper not only help to identify elements of cognitive diversity, they can also be used to help manage conflict. |

| How does cognitive diversity facilitate creativity? |

| Aggarwal, I., & Woolley, A. W. (2019) |

“The paper introduces a new theoretical lens, the signal-detection perspective,

which argues that cognitive diversity amplifies the signals to the location of critical cognitive resources within the team and aids in their detection, consequently enhancing the form of team cognition that is central to team creativity.” |

Cognitive diversity can both enhance and hinder team creativity. |

Investigate how signal detection either generates conflict or provides a way to manage it. |

“Cognitive style diversity introduces differences in

what information team members pay attention to, the

process through which they conduct task work, and

consequently, which strategies they consider important

for task completion.” |

| Kim, T.-Y., David, E. M., & Zhiqiang, L. (2020). |

The study uses a mediating role of motivation and a moderating role of learning. Therefore, it has direct ties to the organizational Communities of Practice. |

The success of cognitively diverse teams is mixed. To improve success, leaders need to create a culture of learning and goal orientation. Leaders can also help facilitate success by asking people to share their expertise. These have direct links to Communities of Practice and Funds of Knowledge. |

Since this research is focused on the Chinese team, future research may want to take the same research techniques and methods and apply them in other cultural settings to see what parts of their conclusions are valid across all cultures and what is isolated to a Chinese culture. |

The study focuses on Chinese teams. Therefore, we may need to isolate the cultural impact to determine direct applicability to our focus. However, the emphasis on motivation and learning have supporting research in western literature and research as well. We can combine them together to build effective Communities of Practice that stimulate creativity. |

| How does cognitive diversity enhance decision-making? |

| Mohammed, S., & Ringseis, E. (2001) |

Examines how individuals entering a group decision-making context with different perspectives of the issues to be discussed arrive at cognitive consensus. Cognitive consensus refers to similarity among group members regarding how key matters are conceptualized and was operationalized as shared assumptions underlying decision issues in the present research. |

“Cognitive consensus refers

to similarity among group members regarding how key issues are conceptualized

and was measured as shared assumptions underlying decision issues. ”

While the study shows how to enhance consensus, it does not tie consensus building to effective decision-making |

Future research should look at the effective diversity enhanced consensus on effective decisions. |

Consensus helps to facilitate decision execution. However, the drive for consensus could create “group think”. Perhaps the greatest value of this study is the signaling approach, which helps to share assumptions and help people to understand each other. This potentially reduces bias, which can inhibit decision-making. |

| Olson, B. J., Parayitam, S., & Bao, Y. (2007) |

“Cognitive diversity has a strong positive relationship with task conflict and that competence-based trust strengthens this relationship. In addition, these results suggest task conflict mediates the effects of cognitive diversity on decision outcomes.”

Task conflict is the mediating variable. How this conflict is managed is key to decision outcome. |

This study provides a direct linkage back to other studies and papers that discuss the impact of conflict on decision-making and success. Here, trust is a key aspect of conflict management. This hearkens back to Covey’s The Speed of Trust and many other works on the effect of trust on organizational success. |

Future research can focus on the impact of cognitive diversion on Information Theory and group processes. How much does diversity enable or hinder processes and how do leaders develop a culture of trust that enables the value of diversity without just blindly accepting that all cognitive diversity is good? How much is trust based on success? |

Cognitive diversity can be a key element that stimulates creativity and decision-making. However, this diversity can engender conflict. Organizations need to develop a culture of trust to channel the conflict into effective outcomes. |

| Pöyhönen, S. (2017) |

The study focused primarily on problems in science and framed the problems by “smoothness” and complexity. |

The study found that cognitive diversity only made a difference in problems that were challenging and complex. In more routine problems, there was no discernable effect. |

Future research can extend this methodology and approach to other applications and fields of study to determine whether they have validity beyond science. |

While the study was focused on science, when viewed with other research, the findings may be valid to any complex and non-heterogenous problem set. Cognitive diversity may stimulate social learning and problem solving in these complex environments were multiple perspectives are needed to understand the problem and solve it |

| Baggio, J. A., Freeman, J., Coyle, T. R., Nguyen, T. T., Hancock, D., Elpers, K. E., Nabity, S., Dengah, H. J. F., & Pillow, D. (2019) |

This paper looks at governing common pools of resources. While the foundational topic is governing the commons found in political science, it may be generalizable to other areas where resources are pooled and need to be effectively distributed, such as matrixed organizations. They use a Theory of Mind that includes cognitive functional traits such as general and social intelligence. |

The study results show that, in less complex situations, high intelligence is sufficient to make effective resource management decisions. However, in more complex situations with intense competition for resources, groups with higher general and social intelligence perform better. |

Future studies can look at the impact of social intelligence on other fields that resource competition and management. This could be linked to future research in the science issue Pöyhönen framed. Can we expand upon the Theory of the Mind and look at it in conjunction with other descriptors of cognitive diversity? |

How does an organization general social intelligence? How much does homogeneity reduce uncertainty and how much does heterogeneity generate different learning heuristics and perspectives that facilitate solving different problem sets. Perhaps organizations can find optimal balancing points. |

| How should an organization manage the conflict cognitive diversity may create? |

| Mello, A. L., & Delise, L. A. (2015) |

“Effects of diversity in team members’ rational and intuitive cognitive styles

Impact on team outcomes were investigated in a moderated-mediation model, exploring conflict management as a moderator and cohesion as a mediator.” |

“The negative effects of diversity on cohesion were moderated by conflict management, such that diversity harmed cohesion when conflict management was low but had no effect when conflict management was high.” |

Future research may focus on how to enable diversity without undue conflict. This may tie into Olson et al and trust. It can also tie into Follet’s concept of creative conflict and how it can be effectively managed. |

Diversity could engender conflict. Follet’s concept of conflict and the various approaches to adaptive and distributed leadership, as well as Communities of Practice and the moderation of discourse and dialog will be key to channeling conflict into productive outlets for creativity and decision-making. |

References

Adler, P. S. (1999). Building Better Bureaucracies. Academy of Management Executive, 13(4).

Adler, P. S., Forbes, L. C., & Willmott, H. (2007). 3 Critical Management Studies. The Academy of Management Annals, 1(1), 119–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/078559808

Aggarwal, I., & Woolley, A. W. (2019). Team creativity, cognition, and cognitive style diversity. Management Science, 65(4), 1586–1599. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.3001

Baggio, J. A., Freeman, J., Coyle, T. R., Nguyen, T. T., Hancock, D., Elpers, K. E., Nabity, S., Dengah, H. J. F., & Pillow, D. (2019). The importance of cognitive diversity for sustaining the commons. In Nature Communications (Vol. 10, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08549-8

Bender, A., & Beller, S. (2016). Current perspectives on cognitive diversity. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(APR), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00509

Douglas, N & Wykowski, T. (2011). From Belief to Knowledge: Achieving and Sustaining and Adaptive Culture in Organizations. CRC Press.

Elmore, R. F. (2000). Building a New Structure For School Leadership.

Follett, M. P. (1995). Mary Parker Follett Prophet of Management (P. Gr & Aham (eds.)). Beard Books.

Fulmer, W. E. (2000). Shaping the Adaptive Organization: Landscapes, Learning, and Leadership in Volatile Times. AMACOM.

Guillaume, Y.R.F., Dawson, J.F., Woods, S.A., Sacramento, C.A. and West, M.A. (2013), Getting diversity at work to work: What we know and what we still don’t know. J Occup Organ Psychol, 86: 123-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12009

Kim, T.-Y., David, E. M., & Zhiqiang, L. (2020). Perceived Cognitive Diversity and Creativity: A Multi-Level Study of Motivational Mechanisms and Boundary Conditions. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 0(0), 1–15.

Lundenberg, F. C. (2012). Power and leadership: An influence process. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 15(1), 1–9.

Mello, A. L., & Delise, L. A. (2015). Cognitive Diversity to Team Outcomes: The Roles of Cohesion and Conflict Management. Small Group Research, 46(2), 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496415570916

Mello, A. L., & Rentsch, J. R. (2015). Cognitive Diversity in Teams: A Multidisciplinary Review. Small Group Research, 46(6), 623–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496415602558

Mohammed, S., & Ringseis, E. (2001). Cognitive diversity and consensus in group decision making: The role of inputs, processes, and outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85(2), 310–335. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2943

Olson, B. J., Parayitam, S., & Bao, Y. (2007). Strategic decision making: The effects of cognitive diversity, conflict, and trust on decision outcomes. Journal of Management, 33(2), 196–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306298657

Pöyhönen, S. (2017). Value of cognitive diversity in science. Synthese, 194(11), 4519–4540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1147-4

Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline (Kindle). Crown Publishing Group.

Spillane, J. P., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. B. (2004). Towards a theory of leadership practice – Spillane, Halverson, Diamond.pdf. J. Curriculum Studies, 36(1), 3–34.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2003). “Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 26(4), 527. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X03210116

Stone, D. (2012). Policy Paradox, The Art of Political Decision Making (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Stoyanov, S., Jablokow, K., Rosas, S. R., Wopereis, I. G. J. H., & Kirschner, P. A. (2017). Concept mapping—An effective method for identifying diversity and congruity in cognitive style. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.015

Yukl, G. (n.d.). Chapter 1 Introduction : The Nature of Leadership and Leadership Research. Leadership in Organizaitons, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2007.4408865