The Rise of the American Bureaucracy

Figure Source: http://clipart-library.com/clipart/rTLobyGkc.htm

The US has had a bureaucracy in one form or another since its founding. For the first 100 years, it was small and appointed by the President or his administration leaders. Pundits called this process the spoils system or patronage and nepotism. It brought us both good service and corruption. For example, the corruption plagued the Grant administration.

Reformers, such as Woodrow Wilson, Max Weber, and Frederick Taylor, sought to improve effectiveness in both the government and private sectors. Wilson sought to replace spoils system with a professional bureaucracy and completely reform including themes from Weber and Taylor.

The assassination of President Garfield in 1881 by a disgruntled civil service candidate provided the impetus for change. The congress passed the Pendleton (Civil Service Reform) Act in 1883. The act stated that hiring and promotion in the civil service be based on merit and distributed throughout the states and territories based on population. It also created the Civil Service Commission.

The next significant milestone in the bureaucracy’s growth was the 16th Amendment in 1913, which brought in the Income Tax and allowed Congress to spend money in virtually anyway they wanted. The federal government now had the funding needed to grow its power, control, and influence. This enabled the advent of the American Empire and Progressivism (see Part 4: The Spanish-American War, the American Empire, and Progressism in the Power Inflection series.

This power, influence, and control allowed the federal government to grow exponentially with Franklin Roosevelt’s New (see Part 5: The New Deal of the Power inflection Series) and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society (see Part 7: The Great Society of the Power Inflection series). The bureaucracy grew in size and power with the programs these presidential campaigns engendered. The figure below shows the growth in Federal, non-intelligence and military employment. This is a good proxy for the size and growth of the bureaucracy. You can clearly see the growth post Great Society.

Figure 2 Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USGOVT

As this power grew, both Congress and the President lost power to the bureaucracy, largely from an asymmetric balance of information as discussed in the theory section below. As their power grew, they captured even more power and control through regulation and the agencies they controlled. In essence, the bureaucracy became an unelected fourth branch of government.

The Pendleton reform came unwound during the Carter Administration in Luévano v. Campbell. This case ruled the Professional and Administrative Careers Examination (PACE) was racially discriminatory since Blacks and Hispanics had lower test score. President Carter scrapped PACE and paved the way for first Affirmative Action and lately Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity (DIE) in the bureaucracy. Effectively, the action gutted Pendleton and promoted people based on demographics rather than merit and ability.

So, as the bureaucracy was getting stronger, Carter threw the reason for the reforms out the window. Unions also came into the federal government, which further lowered effectiveness and made it even more difficult to fire federal workers, The net effect was programs that never end, regardless of whether they achieved their purpose or are so poorly designed and managed they will never achieve their purpose.

In Part 7: The Great Society, I quoted Edwin J. Feulner, in Assessing the ‘Great Society’ which showed the US spent over $80 Trillion on 80 Great Society programs. In Part 2 of the Faustian Bargain series, I presented data that showed these programs created a bevy of social problems, to include an explosion in single-parent households and in an increase in poverty. The $80T made few lives other than the bureaucrats that administer the programs better.

Einstein once said the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Yet the Mad Scientists in the federal government seem to do exactly that. And as the theory section shows, congress and even the president have diminishing power to change their behavior.

The Mad Scientists created an unelected 4th branch of government with little control or accountability with lifelong employment for its members at increasingly competitive wages and benefits.

Theory

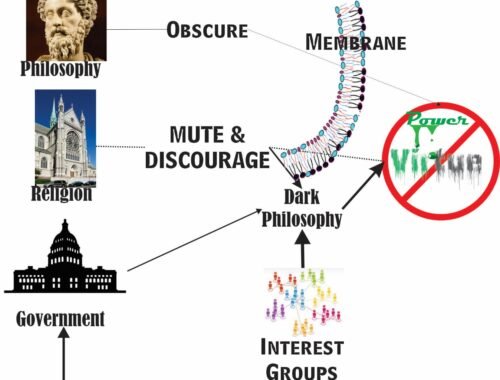

As issues become more complex and the information asymmetries between Congress and the agency increase, congressional control decreases. Congress seeks to rectify this situation and enhance control through broad groups of ex ante and ex post controls, as well as defining the structure of the agency and its processes and procedures. The essence of the literature is to describe how Congress gains and maintains control over the bureaucracy, especially policy setting. Ex ante controls place constraints on the bureaucracy designed to control behavior and policy setting. They include controls, such as process and budget constraints. Ex post controls control the bureaucracy through reporting, congressional hearings, and audits. Congressional controls must allow Congress to shape ongoing policy during a crisis or significant issue. With the State Department, the critical committees are the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. These committees hold hearings and exercise many of the potential ex ante and ex post controls over the State Department.

Moe discusses both ex ante and ex post controls, with a new emphasis on ex ante control (Moe, Forthcoming in 2012). McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast (collectively known as McNollgast) also discuss aspects of political control that are highly relevant to the situation ( McCubbins, et al., 1989). Wood and Waterman also provide a discussion of political control over the bureaucracy (Waterman, 1991) and note policy monitoring would help offset some of the asymmetry of information between Congress and the bureaucracy. This information asymmetry is the root cause of many of the congressional-bureaucracy conflicts and congressional desire to place controls on the bureaucracy. Hook states: “Distrust of the State Department and its diplomatic milieu is deeply embedded in US political culture, never far beneath the surface in Congress, the White House, and other agencies of the executive branch.” (Hook, 2003 p. 23). For example, Rondinelli cites House Committee on Foreign Relations to ensure oversight and control of developmental programs (Rondinelli, 1982).

Huber and Shipan provide an interesting study on congressional policy setting that considers presidential and agency preferences as well. They note that Congress implicitly sets policy preferences that recognize the power of presidential veto and the agencies. Congress understands it cannot arbitrarily set policy and define a structure with impunity (Huber, et al., 2002 p. 105). David Lewis continued the advocacy for presidential control over the bureaucracy. He makes the convincing point that the president is the only nationally elected official and is publicly held responsible for policy and performance (Lewis, 2003). While his work, like many others, focuses more on agency design than policy, he does note:

Agency design determines, among other things, the degree to which current and future political actors can change the direction of public policy by nonlegislative means. Some structural arrangements allow more control by political actors than others do. (Lewis, 2003 p. 3)

Of special note for this study is Lewis’ observation, citing Canes-Wrone et al., that

These advantages [over Congress] are perhaps greatest in foreign policy, where the president exercises independent constitutional authority over foreign affairs and maintains the largest informational advantage of Congress. (Lewis, 2003 p. 74)

References

Hook Steven W. Domestic Obstacles to International Affairs: The State Department under Fire at Home [Journal] // Political Science and Politics, Vol. 36, No. 1. – 2003. – pp. 23-29.

Huber John D. and Shipan Charles R. Deliberate Discretion? The Institutional Foundations of Bureaucratic Autonomy [Book]. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Lewis David E Presidents and the Politics of Agency Design [Book]. – Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003.

McCubbins Matthew D., Noll Roger G. and Weingast Barry R. “Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative Arrangements and the Political Control of Agencies [Journal] // Virginia Law Review No 75. – 1989. – pp. 431-82.

McCubbins Matthew D. and Schwartz Thomas Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols Versus Fire Alarms [Journal] // American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Feb., 1984). – 1984. – pp. 165-179.

Moe Terry Public Bureaucracy and the Theory of Political Control [Book] / ed. Roberts Robert Gibbons and John. – Forthcoming in 2012. – Vol. Handbook of Organizational Economics: p. 2.

Moe Terry M “The Politics of Structural Choice: Towards a Theory of Public Bureaucracy” [Book Section] // Organizational Theory of the Organization from Chester Barnard to the Present and Beyond / book auth. Williamson Oliver E. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Moe Terry The Politics of Bureaucratic Structure [Book Section] // Can the Government Govern? / book auth. Chubb John E. and Peterson Paul E.. – Washington, D. C.: The Brookings Institution, 1989.

Rondinelli Dennis A. The Dilemma of Development Administration: Complexity and Uncertainty in Control-Oriented Bureaucracies [Journal] // World Politics, Vol. 35, No. 1. – 1982. – pp. 43-72.

Waterman Dan B. Wood and Richard W. The Dynamics of Political Control of the Bureaucracy [Journal] // American Political Science Review 85 (3). – 1991. – pp. 801-828.