Operant Conditioning, Path Dependency and Societal Revolution, Part 1

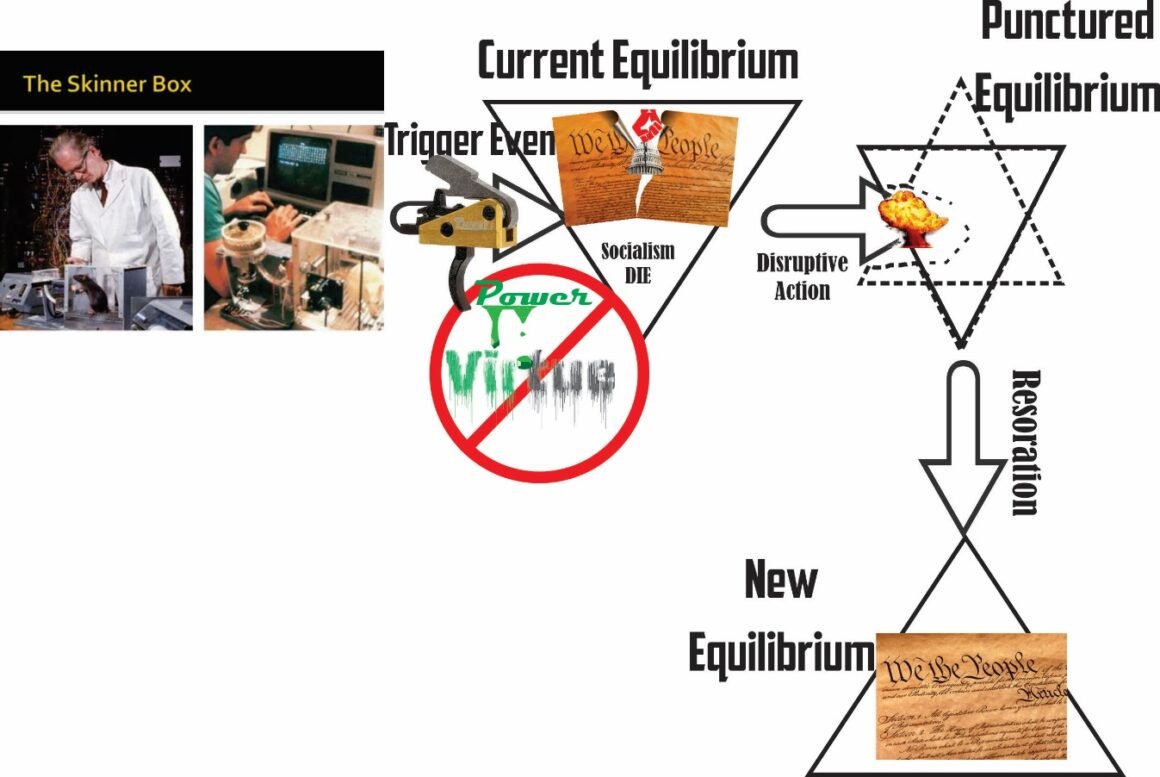

First a disclaimer. I dislike the practice of operant conditioning. It robs a person of their free will and inherently erodes virtue. Now there are some people in the neuroscience community that say freewill does not exist. While I cannot prove it, I think it does. The founders of the US Republic built it on these principles. Erode them, and you erode the foundations of the Republic. Operant conditioning does work, but at what price?

Consider the use of Agent Orange in Viet Nam. It accomplished its defoliation objective and presumably save American lives. But it also killed American soldiers via cancer from exposure to it. Just because something achieves its design purpose does not mean it is effective if the costs exceed the benefits. I suspect that the costs in terms of eroded virtue exceed the benefits. Is the potential dissolution of the Constitution and eroding of virtue and meritocracy worth the adoption of Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity (DIE)?

So what is operant conditioning?

J. E. R. Staddon and D. T. Cerutti in Operant Conditioning wrote:

“Operant behavior is behavior “controlled” by its consequences. In practice, operant conditioning is the study of reversible behavior maintained by reinforcement schedules.”

“The term operant conditioning1 was coined by B. F. Skinner in 1937 in the context of reflex physiology, to differentiate what he was interested in—behavior that affects the environment—from the reflex-related subject matter of the Pavlovians. The term was novel, but its referent was not entirely new. Operant behavior, though defined by Skinner as behavior “controlled by its consequences” is in practice little different from what had previously been termed “instrumental learning” and what most people would call habit. Any well-trained “operant” is in effect a habit.”

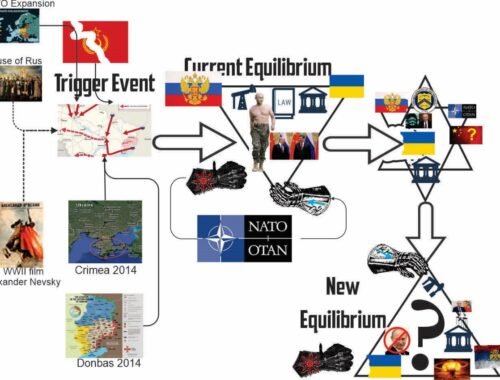

“Habit” is a good word for individuals but may not be the best word choice for organizations and societies. A better term is Path Dependency. Simply put, path dependency is like a pool table with a worn groove in it. The billiard balls fall into the groove and follow it. Unless something happens to either knock the ball out of the groove or the table is repaired to fill in the groove. That event or series of events are a punctuated equilibrium. See the theory notes below for details and the pathbreaking strategy series: part 1, part 2, and part 3.

Virtually all of government’s functions use operant conditioning’s system reward and punishment. James Madison, in Federalist Paper Number 51, recognized this when he wrote:

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controuls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to controul the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to controul itself.”

What he means by “angels” is if people governed themselves by virtue and practiced virtue. The less virtue is involved, the more government rules by operant conditions with reward and punishment molding behavior. The exercise of this power erodes virtue and extends the need for more operant control to make society manageable. See the Power Shift series: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part5 , part 6, part 7, part 8) for examples of the growth of governmental power.

We need a regulator to balance the government’s operant controls and room and encouragement for virtue to grow. The original Constitution struck this balance. We altered the Constitution as discussed in the Power Shift series. The central government grew in power and virtue eroded by this caustic approach to behavior modification. Reward and punishment are the opposite of virtue and, in the long run, are far less reliable. I’ll explore that concept in follow-on parts.

Theory notes

Path dependency theory originated in economics, but political science adopted it. The theory states that correlations between future actions and past events influence where an organization/institution can and will go. From an economic perspective, Stack and Gartland note, “The relative strength of this type of path-dependent analysis is in showing the dynamic evolution of an industry to a path of sub-optimality” (Stack, et al., 2003). Spruyt and others note the observation is equally relevant to political science, and path dependency is a recognized and accepted explanatory factor used in political science (Spruyt, 1994). It is a fundamental part of the historical institutionalism school, which is an integral part of this analysis and differs from a strict logical causal model.

Institutions—organizations, systems, and policies—find equilibrium points and stay there unless knocked off it. That is the essence of path dependency. The past shapes the future until a trigger event happens that creates a punctured equilibrium.

Punctuated-equilibrium theory seeks to explain a simple observation: Political processes are generally characterized by stability and incrementalism, but occasionally they produce large-scale departures from the past. Stasis, rather than crisis, typically characterizes most policy areas, but crises do occur. Large-scale changes in public policies are constantly occurring in one area or another of American politics and policymaking as public understandings of existing problems change. Important governmental programs are sometimes altered dramatically, even if most of the time they continue as they did in the previous year. While both stability and change are important elements of the policy process, most policy models have been designed to explain, or at least have been most successful at explaining, either the stability or the change. Punctuated-equilibrium theory encompasses both. (True et al., 2007)

When combined with path dependency theory, the two show that paths that provide desired outcomes are successful and reinforce path dependent lock in (Pierson, 2000). However, as Stack and Gartland observe, a once positive path can turn sub-optimal, yet be difficult to change because of lock-in. Exogenous events that create a punctuated equilibrium may be the only way to break this lock-in (Spruyt, 1994, p. 23). Researchers in the social sciences often link path dependency to historical institutionalism and cite it as a weakness of the school (Peters, et al., 2005). However, when the punctuated equilibrium effect is considered, the school allows for institutional change and provides an interesting model.

Punctuated equilibrium refers to events that can significantly alter a path and cause an actor to re-evaluate policy and actions. Spryut notes:

Change in institutions imposes costs, and hence social groups and political actors will be unwilling to experiment with new institutions unless a serious exogenous shock alters political alignments. Units will otherwise continue in the form they have taken at a particular historical juncture. Change will take the form of a punctuated equilibrium—a dramatic shift along several dimensions simultaneously in response to a powerful environmental change. (Spruyt, 1994 p. 7)

Bennet and Elman’s study of path dependency is especially relevant to the case at hand. They discuss using qualitative methods to address path dependencies (Bennett, et al., 2006) and a systematic set of case studies to determine path dependence. Since path dependency comes from economics and historical sociology, they note that there are different views and definitions. They highlight four key areas, however, that seem to be common: causal possibility, contingency, closure, and constraint. The first three areas allow for multiple potential paths organizations can pursue and provide for potential path changes. Constraints, however, tend to lock institutions into a specific path. This may be from increasing returns associated with the path or from norms and values that develop within the institution that favor the path. As noted by Hall and Taylor, norms and values are important in institutional analysis. This notion will be important as we apply path dependency theory to the case at hand.

References

Bennett, Andrew and Elman, Colin (2006). Complex Causal Relations and Case Study Methods: The Example of Path Dependence. Political Analysis, Vol. 14, No. 3, Special Issue on Causal Complexity and Qualitative Methods (Summer 2006). pp. 250-267.

Hall, Peter A. and Taylor, Rosemary C. R. (1996). Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms. Political Studies Vol. 44. – pp. 952-973.

Peters, B. Guy, Pierre, Jon and King, Desmond S. (2005) The Politics of Path Dependency: Political Conflict in Historical Institutionalism. The Journal of Politics. pp. 1275-1300.

Spruyt, Hendrik (1994). The Sovereign State and its Competitors. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stack, Martin and Gartland Myles P (2003). Path Creation, Path Dependency, and Alternative Theories of the Firm. Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Jun., 2003). – 2003. – pp. 487-494.

True, J. L., Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2007). Punctuated-Equilibrium Theory Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking. In Theories of the policy process (Issue April, pp. 155–188).

2 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback: