Power Shift, Part 2: Judicial Review

The constitution is either a superior paramount law, unchangeable by ordinary means, or it is on a level with ordinary legislative acts, alterable when the legislature shall please to alter it. It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. This is the very essence of judicial duty. John Marshall

Abstract: The Constitution does not support judicial review. Article III of the Constitution (Judicial branch) is the vaguest part of the Constitution and leaves much open to interpretation of English Common Law.

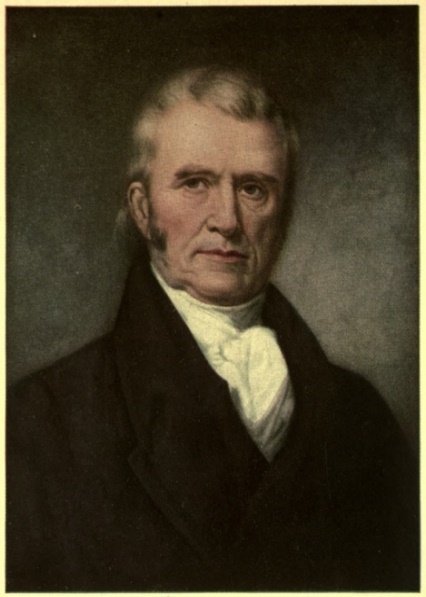

Judicial review did not directly transfer power from the states to the federal government, but John Marshall’s fiat proclamation of judicial review in 1803, during Marbury v. Madison, set the groundwork for this transfer. Judicial review has been used, in conjunction with a stronger bureaucracy (discussed in part 4 of this series), to overturn state and federal laws and executive decisions. Potential court vacancies can shape presidential elections and decisions. Yet nothing in the Constitution provides for judicial review. Article III that discusses the judiciary is vague in many areas.

I first looked at the concept of judicial review in my law course at West Point. I loved the course, but knew I did not want to be a lawyer. The course provided an excellent overview of Marbury v. Madison, the case that established judicial review. I looked at Marbury v. Madison from multiple points of view and the Constitution and never could understand how my (possible) kinsman came up with judicial review. Then I came across an assessment from Cornell Law School that said the concept came not from the Constitution, but rather from Federalist Paper 78. In this paper, Hamilton wrote:

The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is in fact, and must be, regarded by the judges as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcileable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought of course to be preferred; or in other words, the constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Things that make you go hmmmm. The source that makes the judiciary the arbitrer of constitutionality is not the Constitution. It is at best a design document and at worst a hype piece used to garner support for the Constitution’s approval. I do not mean this to take anything away from Hamilton, who did a masterful job of explanation in the Federalist Papers. But his comment quoted above is not in the Constitution. Hamilton may have wanted it in there, but it did not make it. What Marshall did was take a well-articulated concept and turn it into a tool to turn the weakest of the triad of government into a powerhouse. And Marshall not only got away with it, but the judiciary extended the concept and its power to lower courts.

Now perhaps the Constitution needs something like judicial review. But I ask, if the founders thought so, why was it not included in Article III of the Constitution or in the 11th Amendment (1794) which amended Article III, section II? Or why was it not added after Marbury v. Madison in 1803, perhaps as part of the 12th Amendment? The 12th Amendment was proposed December 9, 1803, after Marbury v. Madison. Instead, Congress and the Presidency simply accepted Marshall’s fiat.

The next curious aspect of the judiciary is in Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution: “The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour…” The term itself is from English law and means a lifetime appointment. But what constitutes “good behaviour”? Under English law, a judge could be removed by a joint action of the executive and the legislature or by the judiciary. If the source for good behavior is English law as cited by many sources, then perhaps the judicial removal process is the same as English law.

Article III is curiously vague. It uses the “good behaviour” language and does not set the number of supreme court justices. This vagueness provided Franklin Roosevelt with an opportunity to “pack” the court by adding more justices that would be favorable to the New Deal. His own party helped to defeat this idea. Now, the Democratic Party has resurfaced the idea.

Given the amount of judicial activism on the part of both parties and at least two Supreme Court judges who held on well past their ability to reason soundly, perhaps it is time to review Article III. As a minimum, this review should include:

- What constitutes “good behavior”? What are the mechanisms to remove a judge? Can we consider a judge that is so old he or she continually falls asleep during court or exhibits signs of diminished mental to fall outside the limits of “good behavior”? Can a judge that rules contrary to the Constitution, or ignores it completely be outside limits of “good behavior”?

- What should the number of justices on the Supreme Court be? Is it dangerous to leave this open to court packing by any political party in power?

- Should the judiciary have judicial review?

These are important questions, especially now. For example, the Affirmative Action Alliance says, “The Constitution is no longer relevant in most proceedings taking place in any Federal, State or County Court in the U.S.A.”

Harvard Law Forum had this to say a few years ago:

Just a few days before this journal published Professor David Strauss’s excellent Foreword suggesting that constitutional text matters little to constitutional law, Judge Richard Posner, the most cited legal scholar of our generation, Fred R. Shapiro, shocked many academics attending a constitutional law conference at the Loyola University Chicago School of Law. Judge Posner said that when he decides cases, he does not care what people in the late eighteenth century thought about today’s legal issues or even what the constitutional text says about those problems. He remarked that following the Constitution does not mean adhering to its text but instead respecting Supreme Court interpretations of that text. Constitutional law as made by judges, Judge Posner emphasized, is much more about creating rules that make sense today than interpreting an old and often obsolete document. He concluded the following:

If you look at the entire body of constitutional law, that body of law bears very little resemblance to the text of the Constitution in 1789, 1791, and 1868. . . . That’s the reality. The only useful way to advocate with regard to constitutional law is to give a good contemporary argument for or against a particular interpretation.

We span the gamut from a possible fringe element suggesting the Constitution is no longer relevant to perhaps the preeminent law school suggesting that an unelected body can shape the Constitution to mean whatever it wants it to mean. In this day of judicial activism, we all need to understand what the Constitution does and does not say and set written answers to the three questions above.